Why Excitement Shouldn’t Replace Connection in the Digital Classroom

If you know me, read my blogs or my recent book, you will undoubtedly be aware that I am a huge advocate for EdTech and have always encouraged the use of tech in the classroom. There’s no doubt technology has transformed our classrooms. From 1:1 iPad programmes to immersive augmented reality experiences and gamified retrieval tools, we’re teaching in an era of possibility that is expanding rapidly.

But when every lesson risks becoming a digital event or a competitive quiz, we need to pause and ask: what will children actually remember? The disciplinary knowledge we intended to teach or the rush of novelty?

This tension isn’t just present in the classroom; it’s amplified by social media. Increasingly, teachers are sharing TikToks or Instagram Reels documenting their classroom walk-ins, photocopying sessions, or beautifully decorated displays, often set to upbeat music and captions like “a day in my life as a teacher.” While these posts are well-intentioned, they can unintentionally promote a version of teaching centred around aesthetics and excitement, rather than pedagogy and purpose. It frames visibility as value, suggesting that what is most engaging to watch is also most effective for children. But teaching isn’t a performance. It’s a practice, and often, the best teaching moments don’t make for captivating content. This is particularly damaging when viewed by new teachers or those considering entering the profession. Given the huge retention and recruitment crisis in education, we do not need more gloss; we need clear, honest realism. However, this doesn’t need to be a negative. Teaching is hard, very hard, but it is 100% an incredible profession that is hugely rewarding in so many different ways, and I don’t think we share all that makes it great.

Are We Solving the Wrong Problem?

So much of the current drive toward gamification, interactivity, and AR/VR immersion stems from a belief that children are bored, disengaged, and therefore need to be entertained. This criticism is often levied at the ‘overstuffed’ curriculum. However, if you have ever read it (with the exception of maths and English), the curriculum is far from overstuffed, in my opinion. It is, though, grossly misinterpreted.

I’ve said it before in a previous BLOG POST we do not need to hide our subjects behind a veil of gimmickry. They do not need to be wrapped in a bright, colourful package to be worthwhile. Curriculum subjects — when thoughtfully sequenced and purposefully taught – are inherently creative and exciting. The challenge is not in making them more entertaining, but in giving them the professional attention they deserve as leaders and practitioners. Too often, we farm out subject integrity and progression to wholesale providers claiming to offer “high quality” and “low workload” solutions – when in reality, they’re offering mass-produced content with minimal thought and zero professional judgement.

Ultimately, we are now also in danger of reducing education to fast-paced ‘YouTube Shorts’. But what if boredom is not the problem we think it is?

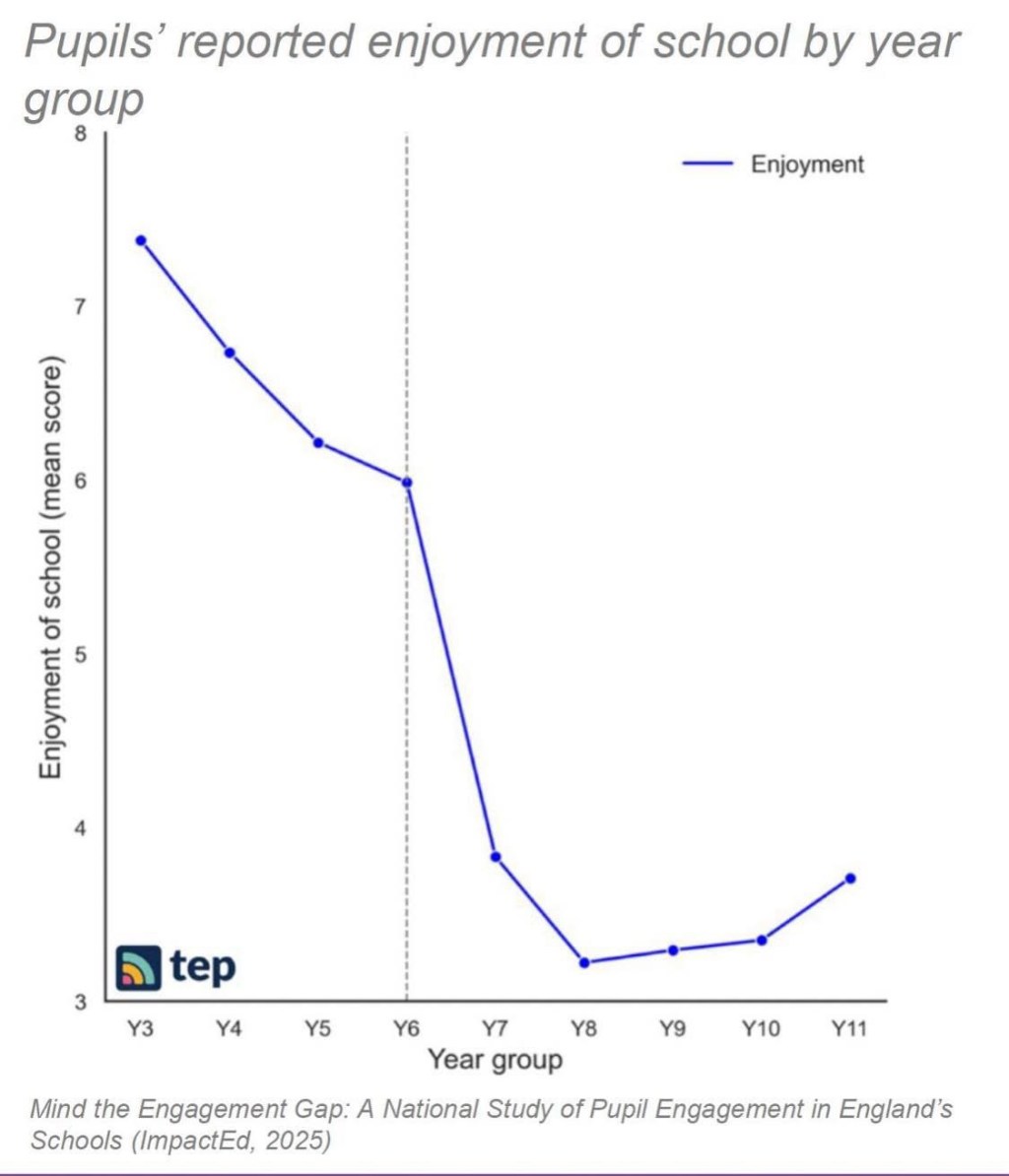

Research in neuroscience has recently suggested that the appearance of boredom in children, particularly from screen-saturated cultures, may be a symptom of dopamine desensitisation, not a lack of stimulation. I have been listening to psychiatrist Dr. Anna Lembke’s (2021) audiobook on Spotify Dopamine Nation, and she has claimed that repeated exposure to fast-paced, highly stimulating digital media (e.g., TikTok, YouTube Shorts, Fortnite) can reduce a child’s threshold for reward. This could mean ordinary classroom activities, among other things, may feel “boring” simply because they are not delivering the same dopamine spike.

This isn’t a failure of teaching. It’s an evolving biological adaptation to overstimulation.

We’re also seeing a marked rise in school refusal and attendance issues, particularly post-pandemic. I am not at all suggesting that this is the reason for attendance issues; however, it is worth noting that this may have a contributing impact, alongside the many other factors. Some children are reporting feeling overwhelmed or “bored” by the classroom, but again, this may not reflect the quality of the teaching. Instead, it might indicate that the pace, predictability, and cognitive demands of the classroom stand in stark contrast to the sensory immediacy of online life. For these children, disengagement may not be about boredom at all, but about withdrawal.

So rather than competing with social media for children’s attention, our job in schools is to recalibrate what learning feels like.

Education is not a dopamine-driven game loop; it is the slow, deep, sometimes effortful construction of meaning over time.

Framing It with the EEF’s Guidance

The Education Endowment Foundation’s (EEF) guidance report on digital technology has always provided a helpful lens through which we should evaluate the impact of technology. It sets out quite a lot, however, I have paraphrased and summarised into these four evidence-informed principles:

1. Does it support effective pedagogy?

2. Does it help pupils practise and consolidate learning?

3. Does it improve assessment and feedback?

4. Does it improve access to learning for all pupils?

If we run many current tech trends through that filter, whether it’s AR field trips, Blooket quizzes, or interactive VR timelines – we often find alignment with engagement and access, but far less evidence of long-term learning impact. They haven’t been designed or mapped out to progress; they have been designed to enhance a moment, which is, of course, fine in and of itself. However, we need to take the care to actually check that this is an appropriate enhancement or if a high-quality image or artifact is better?

Gamification – Helpful Practice or Harmful Substitution?

Retrieval practice has a strong evidence base. You will also undoubtedly know that I am a huge, huge fan of retrieval tasks – they are genuinely one of my favourite tasks to design. I also love low-stakes quizzes, self-testing, and spaced tasks. However, I would urge caution when these are packaged in fast-paced, high-stakes, gamified platforms because the focus subtly shifts. The goal becomes winning, not remembering.

I love Blooket, the children love Blooket, and it is 100% an engaging tool – but are they rehearsing the knowledge or rehearsing how to win the game? Each time I use Kahoot or Blooket, the focus shifts entirely. It ends up descending into a chaotic scene of colours and gold-stealing.

A 2022 study by Sailer and Homner, published in Educational Psychology Review, found that gamification improves motivation in the short term, but its impact on actual learning is mixed. The key issue is alignment – if the game structure overshadows the learning intention, cognitive energy is spent on the gameplay strategies, not the content acquisition.

For me, a high-quality alternative would be something like WordWall. There is enough interactivity to make it engaging, but it can be aligned very easily to your learning intentions. I would also recommend Socrative for low-stakes, simple quizzes.

AR and VR: A World of Possibility, or a Layer of Distraction?

Immersive experiences have their place. In geography or history, they can provide context and atmosphere. But they can also reduce complex disciplinary thinking to a visual spectacle.

There are many platforms offering sleek platforms and 360-degree augmented experiences of ancient civilisations. Impressive, yes. But if the takeaway from a lesson on Ancient Egypt becomes the ‘wow’ of seeing pyramids through a screen, rather than the inquiry into why the civilisation developed in that way, we’ve created a memory of the experience, not the knowledge. We want the children to use the visuals to help contextualise and clarify not shock and awe. We can’t forget that the EEF reminds us, “Digital technology should be used to supplement, not substitute for, high-quality teaching.”

Curriculum Comes First – We Are Not the Algorithm

We need to remind ourselves that our job is not to compete with TikTok. We are not in the business of creating algorithmic loops of stimulation. Our classrooms are not platforms for personalised dopamine delivery.

Instead, we offer something far more powerful: the opportunity to develop schema, secure core knowledge, and build fluency across disciplines. This is the purpose of a knowledge-rich curriculum — not to dazzle, but to deepen. Again, before we start saying that this is boring, we need to remember that it is knowledge that allows us to move beyond where we are.

That doesn’t mean technology has no place. Far from it. When aligned with well-sequenced content and thoughtfully designed tasks, it can reduce barriers, enhance modelling, and extend practice. For example, I have begun working closely with two technology companies on completely different ends of the spectrum.

The first is through EduPeople VR, an educational VR experience provider run by Justin Peoples – a former headteacher and incredibly thoughtful practitioner.

He is passionate about creating VR experiences that are memorable but meaningful, which is why I am assisting him in the design of high-quality tasks to work alongside the experience. This ensures rigour while taking children to places they wouldn’t ordinarily be able to go.

Secondly, I have begun to consult with Chalk.ai on the tasks they generate with their incredible resource model – a company that is using A.I. to generate high-quality, deep-thinking templates that can be used to encourage a real connection to the content, instead of mass-produced resources.

Increasingly, the term “Victorian-style education” is used on social media to dismiss traditional, knowledge-led teaching as outdated or joyless. But what’s rarely acknowledged is that clarity, structure, and rigour are not relics of the past – they are what many children need most in a world of digital overstimulation. The goal isn’t to regress to rote learning, but to reclaim the power of secure knowledge in a curriculum that doesn’t rely on constant novelty to maintain attention.

But the moment technology becomes the task, or the reward, we risk hollowing out the curriculum from within.

AI in the Classroom

I’m optimistic about the role AI can play in teacher workload reduction and curriculum development. Tools like ChatGPT, Copilot or MagicSchoolAI, when used responsibly, can streamline planning, generate examples, and even support adaptive scaffolding.

But I don’t believe AI should be a learning tool for children, especially at primary level. The early years of education are for constructing foundational knowledge – not for offloading thinking to predictive systems. Children must have time to form, revise, and articulate their own ideas before being exposed to generative shortcuts.

I recently came across a widely shared Instagram post that, while cautious, ultimately leaned towards accepting AI as a classroom tool for children – citing the speed of change and “keeping up” as justifications. This mindset is becoming increasingly common: a quiet resignation to inevitability rather than an informed decision grounded in pedagogy. The issue I have with posts like this is that it leans in heavily to the use of A.I. As a live modelling or misconception illumination rather than focussing on high quality modelling. There are copious examples of teachers suggesting that we should be using ChatGPT as a tool to ‘teach’ children and utilise AI generated feedback. I just do not think it should become part of our arsenal. If you consider where ChatGPT, LLMs and AI tools where a year ago we are very quickly adopting everything with A.I. without truly considering the repercussions both short and long term. But the pace of technological innovation shouldn’t pressure us into choices we haven’t properly evaluated. If the curriculum is the compass, then fear or even excitement should not steer the ship.

Learning That Lasts, Not Moments That Fade

In an age where everything competes for attention, the real gift of the classroom might be the opposite of stimulation: it might be stillness, clarity, and thought.

So yes, use iPads. Use digital tools. Leverage what technology can amplify. But always ask:

- Does this serve the learning?

- Is the task still doing the cognitive work?

- Will the child remember the content, or the novelty?

Let’s not mistake what is possible for what is purposeful. Because as Jeff Goldblum from Jurassic Park reminds us:

“Your scientists were so preoccupied with whether or not they could, they didn’t stop to think if they should.”

The same applies to the classroom.

Do you agree? Disagree? Why? All comments or criticisms welcome.

MRMICT (Karl)

Leave a reply to Laura James Cancel reply