Scott McCloud’s Making Comics might seem an unlikely source of inspiration for a teacher reflecting on curriculum task design, but it has crystallised for me what I believe to be essential principles in designing tasks that engage children meaningfully. Comics, as McCloud illustrates clearly, are a visual medium, but the process of creating and understanding them involves far more than just drawing.

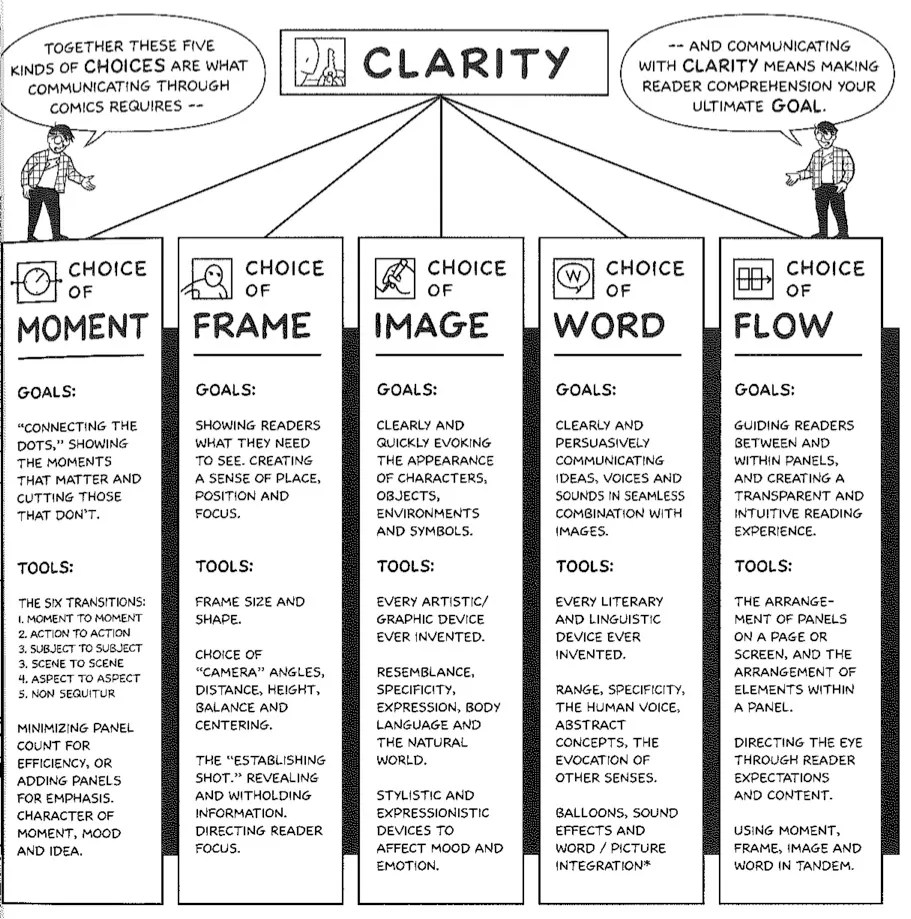

At its core, comics are about the beautiful clarity of storytelling—communicating a story or concept through deliberate choices of moment, frame, image, word, and flow. When rereading his book recently, I realised how much McCloud’s ideas resonated powerfully with my approach to task design in the classroom when I was reminded of his incredible ‘Clarity Diagram’. I loved making comics when I was younger and as an avid comic reader I was also keen to enter this arena. A friend bought me a copy of Scott McCloud’s ‘Making Comics’ a few years later and when I had the time to unwind (pre children) I would often draw and draw comics. I was sorting some of my books when I found Scott’s incredible book and I had a fairly interesting lightbulb moment. Let me explain and provide clarity.

Scott McCloud’s clarity diagram is all about striking a balance between making something easy to understand and making it impactful. On one side, there’s clarity—keeping things straightforward so the message is unmistakable. On the other, there’s expression—adding depth, style, and a touch of intrigue. This made me realize that this balance is something teachers and curriculum designers strive for daily. It involves considering each lesson element’s role in communicating content effectively while still engaging curiosity. The goal? To craft experiences that students not only understand but also remember, making learning both accessible and meaningful. By ‘remember,’ I don’t just mean experiential or exciting (although learning should be); I mean truly remembering and making connections that last.

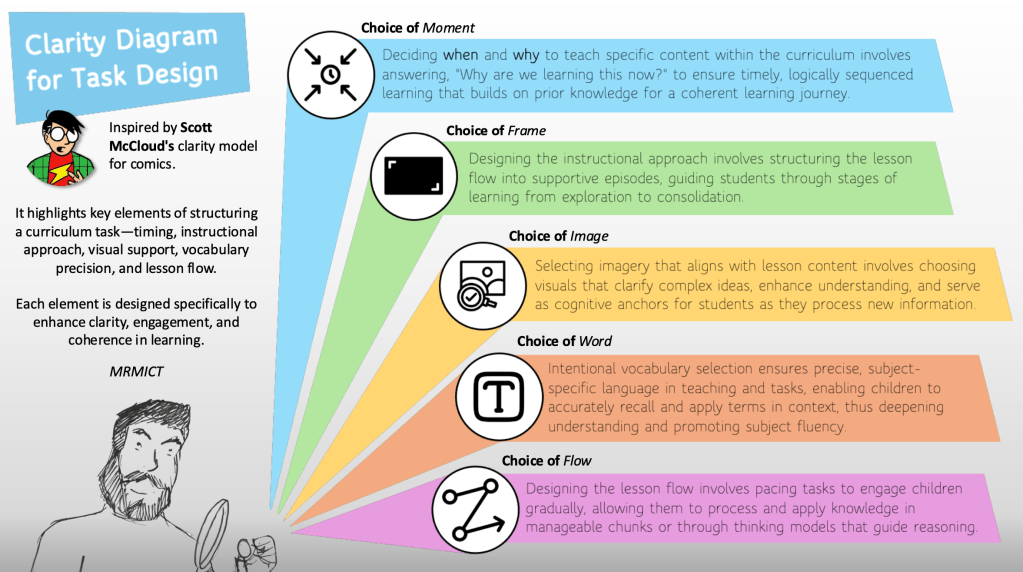

So I decided to see if I could adapt this to fit the curriculum, classroom and task design. Below is the result:

The link here will take you to a far better quality version… although its been a while since I drew a proper ‘self-portrait’ ha ha. I felt it necessary given the art form it originated from.

So where do you start?

Choice of Moment: Why Are We Learning This Now?

In Making Comics, McCloud emphasises the importance of selecting the right “moment” to illustrate, connecting the dots between scenes while cutting out what isn’t essential. In the curriculum and task design, I see a direct parallel.

The “choice of moment” to me represents the decision about why we are teaching something at a particular point in a sequence. Is it the right time for this knowledge or skill to come into focus? What foundations have been laid that will allow children to access this new learning? This reminds me to always ask: why? Making these thoughtful choices ensures that tasks are positioned within a coherent narrative of learning.

This can be as simple as we are teaching toys in year 1 because it is a clear, accessible and tangible way to demonstrate the complicated concept of chronology to small children. We can then build on this each year. This could also be how we structure our curriculum, for example before children learn about the water cycle in geography to they have the appropriate scientific understanding to comprehend it?

Choice of Frame: How Do We Build the Lesson?

McCloud describes the “choice of frame” as determining how much or how little of the action we show — how we draw attention to the things that matter. In the classroom, I believe this is akin to how we design our instructional approach.

The frame represents the structure of the lesson itself, how episodes of teaching and task unfold. For example, are we focussing on the right element at the right time to correctly build fluency and understanding? I would assert that this also includes how much or little we lean into developing a disciplinary approach within a lesson versus how much of the substantive content we build.

Is the talk carefully crafted to support deeper thinking? Are tasks manageable and scaffolded in a way that draws children’s attention to the key learning? Just like a comic panel directs the reader’s focus, the structure of our lessons directs children’s cognitive energy, ultimately helping them navigate from surface understanding to deeper engagement.

Choice of Image: Visual Iconography in Learning

Comics rely heavily on imagery to evoke meaning quickly and clearly, a practice McCloud refers to as “visual iconography.”

This has a clear place in classroom task design. I would also credit Oliver Caviglioli here, as his work on translating Allan Paivio’s dual coding theory into a workable approach for teachers has informed my task design enormously.

Whether we’re talking about icons, diagrams, historical maps, or visual scaffolds for writing, the use of clear, intentional imagery is a powerful teaching tool. Children, like comic readers, use images as cognitive anchors to support their understanding and it helps as a reference back and forth.

Within school, if we refer to concepts like conquest or monarchy, I would always argue we should use the same icon from the second it is introduced until the children leave. We can then apply new layers to this as the children develop schema. However, this doesn’t mean flooding them with random pictures from Google. I would also insist that where there is a specific real world tangible example, such as a historical source or religious artefact we use this as opposed to some carbonised depiction.

The ‘choice of image’ must be deliberate and purposeful, aligning with the content and helping children make connections between the visual and conceptual aspects of the lesson. This is especially important in today’s continuously visual world, where children often learn better when they can see and interact with representations of complex ideas. This is not, I repeat NOT, any justification of ‘visual learners’ this is not at all what I am saying, however, the visual provides clarity with to the abstract.

Choice of Word: Vocabulary as a Tool for Deeper Thinking

McCloud talks about the importance of pairing the right words with images to convey a message effectively. In task design, ‘choice of word’ refers to the language we use to present new ideas and frame children’s tasks. I often draw on the work of Alex Quigley, particularly his book Closing the Vocabulary Gap. The explicit teaching of key vocabulary is critical for unlocking children’s understanding across the curriculum.

Quigley stresses that vocabulary isn’t just about knowing words in isolation, such as through spelling tests. Instead, understanding words through morphology (the structure of words) and etymology (the origin of words) is far more significant, as it unlocks doors to new vocabulary built from the same prefixes, root words, or suffixes.

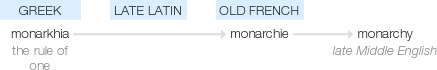

For example, in history, we recently taught the word “monarchy.” What was interesting was breaking it apart and discussing it. It not only involves explaining its meaning but also exploring its roots—mono- (one) and -archy (rule or power).

The children began connecting “monarchy” to “Monday.” While incorrect, as they assumed “Mon” meant first or one, this discussion allows us to clarify what the word does and doesn’t mean. By exploring its Greek or Latin roots, children develop a more nuanced understanding. This helps them not only understand monarchy but also apply this knowledge to other words like oligarchy, heptarchy, or anarchy.

Quigley advocates for deliberate, repeated exposure to key terms, using morphology and etymology as tools for empowering children to engage critically with academic language. This transforms vocabulary from something abstract and unconnected to something more specific and accessible.

Choice of Flow: The Journey Through the Lesson

Finally, McCloud’s “choice of flow” refers to how readers move through a comic—how their eyes are guided from panel to panel, ensuring a smooth and intuitive reading experience. In teaching, it’s my belief thatthis translates to how we design the flow of lessons and tasks. Are we moving children through ideas at the right pace? Have we sequenced tasks so they build in complexity and scaffold learning?

The flow of a lesson also can involve how we are breaking tasks into manageable chunks or are we using thinking models and frameworks that help children process content piece by piece, rather than feeling overwhelmed by a monolithic block of knowledge or writing. Just as comics guide readers seamlessly from one panel to the next, lessons should guide children through stages of understanding without spoilers or overwhelming them.

Task Design as a Visual Medium

Clearly what I am saying is, like comics, task design is a visual and cognitive experience. We are not just presenting information for children to recall; we are guiding them through a journey of understanding, using deliberate and thoughtful choices of moment, frame, image, word, and flow. McCloud’s work has reaffirmed for me that task design—like creating comics—is about much more than just assembling parts. It’s about intentionality and clarity in communicating complex ideas in ways that children can engage with deeply.

Just as McCloud’s comics are designed to make the reader’s experience seamless and meaningful stories and actions, task design should make the child’s learning experience clear, manageable, and encourage deeper thinking.

In both comics and task design, it’s the choices we make that shape the experience and how the knowledge is contracted in the children’s mind. Each element, whether it’s the sequencing of lessons, the vocabulary chosen, or the visual resources used, plays a hugely important role in shaping how children engage with content.

I hope it enlightens some and happy to receive constructive feedback or criticism, as we are all forever learning.

Thank you for reading,

Karl (MRMICT)

Leave a reply to Claire Myers Cancel reply