Why triangulation, not recording, offers a clearer picture of learning

I have been asked questions and having discussion about assessment a lot over the last month, and interestingly we have been fortunate enough to have Clare Sealy provide us with some really interesting CPD that has helped me articulate the concept of assessment with much greater clarity over the past few weeks. Interestingly, I get asked a question regularly: “How do we assess meaningfully in the wider curriculum?” It’s a question that has lots of different answers depending on contexts and viewpoints towards curriculum and assessment generally.

The more I think about it, the more I come back to one principle. Recording data or outcomes is not the same as assessment. Triangulation gives us the insight we actually need.

Why does this question actually matter?

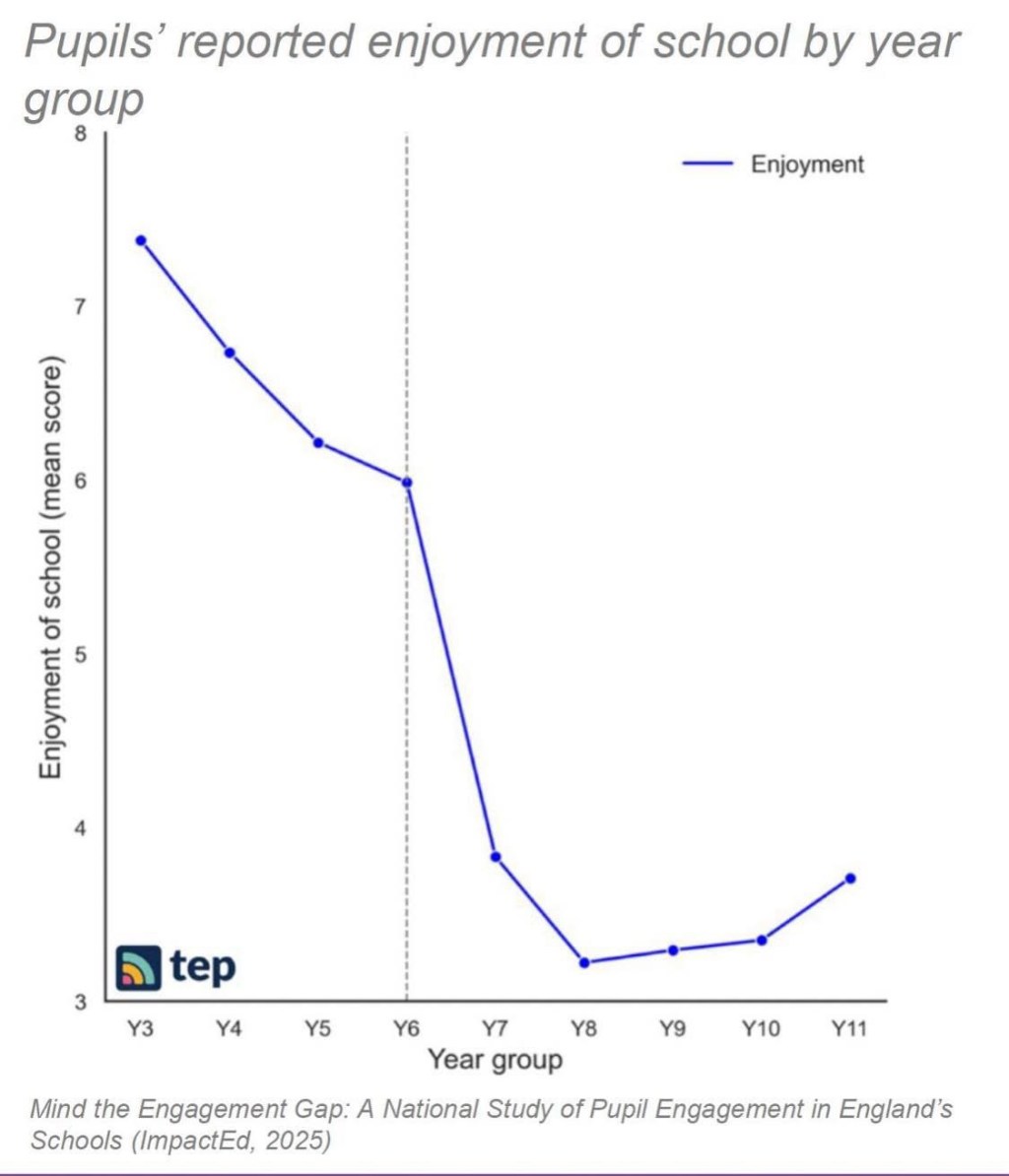

We have this desperate need to quantify almost everything. If a child can’t articulate specific words or tick the right box, then they haven’t properly learned something. Now, I have said a few times before, in primary in particular, the wider curriculum, history, science and geography etc. is about teaching children to make connections, which is why there is significant overlap in geography and science. We’re forming a solid understanding of the world around us and how the past shaped it. So therefore we need to reconsider how we assess in primary because what I hear and see are schools trying to assess in a way that is very secondary.

What’s more is teachers often feel the pressure to produce something tangible when assessing history, geography or science. The assumption is that assessment requires some form of product. I recognise this because I once created those same long WTS, EXS and GDS spreadsheets for foundation subjects based on single pieces of writing or isolated tasks. They looked organised but did very little for curriculum thinking or children’s learning. However, they ‘justified’ the assessment task and gave a very clear impression that children learned something. The problem though is that then the next history unit is very different, or even next year; what were we doing next? How were we showing clear progress?

Clare Sealy’s reminder was that assessment is inference. This really helped me see the problem more clearly. In the wider curriculum we do not test children in the same way as maths. We are inferring their understanding by piecing together multiple forms of evidence.

Now, as well as using final assessment tasks, we also use Pupil Book Study to assess the quality of the curriculum and the teaching. What stuck and why? Clare’s point aligns well with the Evaluation–Analysis–Action cycle that underpins Alex Bedford’s Pupil Book Study. We learn the most when we triangulate what we see in children’s books, what they say, and what they can explain in a structured conversation. No single piece of work can tell the full story, and just because we’ve coloured a cell in a spreadsheet green does not mean we have fundamentally assessed the children.

What is triangulation?

Triangulation in this context refers to gathering multiple forms of insight from different sources such as:

– what the children produce in tasks that are well aligned with the curriculum sequence

– informal talk and structured dialogue with the children about their work and the imagery used in lessons

– prior work completing retrieval tasks

– what appears through any additional assessments such as quizzes etc.

The combination of all of these offers you a more reliable view of what children know and can do. Each piece of evidence allows us to infer something distinct. This helps us build a clearer picture. I use the word clearer because ultimately we can never truly know, as Clare said we are making multiple inferences.

Recording on its own falls short

Recording often becomes a bureaucratic act rather than a professional one. When we generate lists of judgement codes, we encourage the illusion that learning can be summed up in a category detached from context. Tom Sherrington and Dylan Wiliam have both written extensively about the risks of pseudo precision. When judgements are based on single tasks, the reliability of the data collapses.

The wider curriculum requires a different stance. Substantive knowledge and disciplinary knowledge develop across a sequence. Learning is not captured in a single snapshot. The assessment should reflect that complexity.

Designing assessment tasks that reveal thinking

The most useful evidence I gather comes from tasks intentionally designed to reveal conceptual links. These tasks come directly from the curriculum sequence rather than being bolted on.

Examples within my own practice

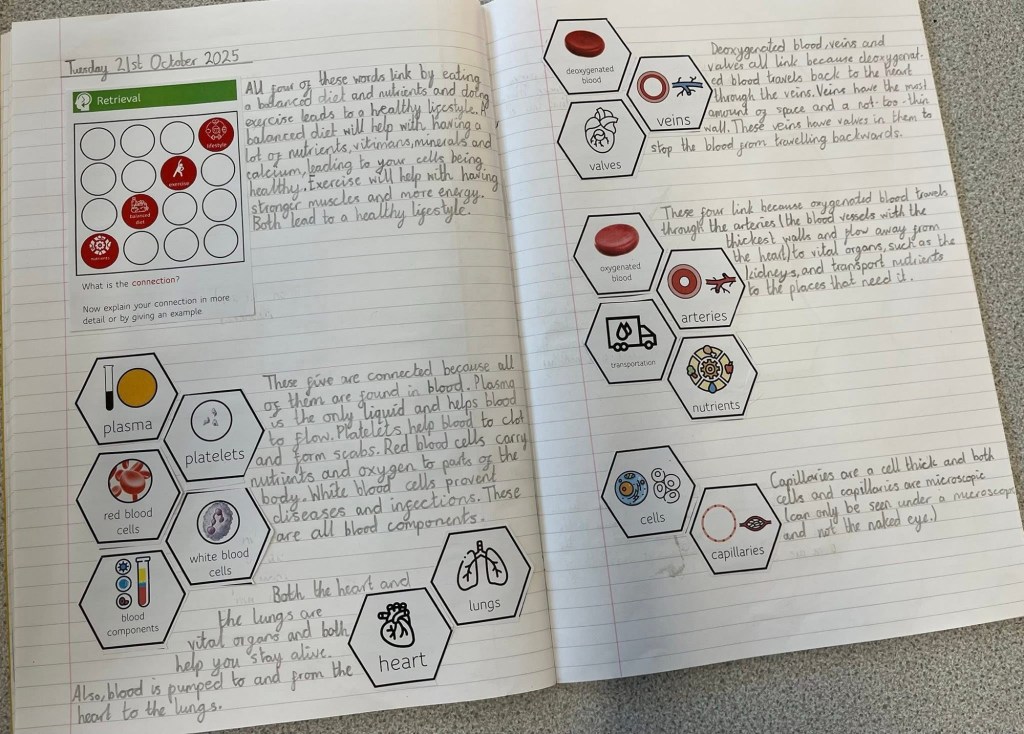

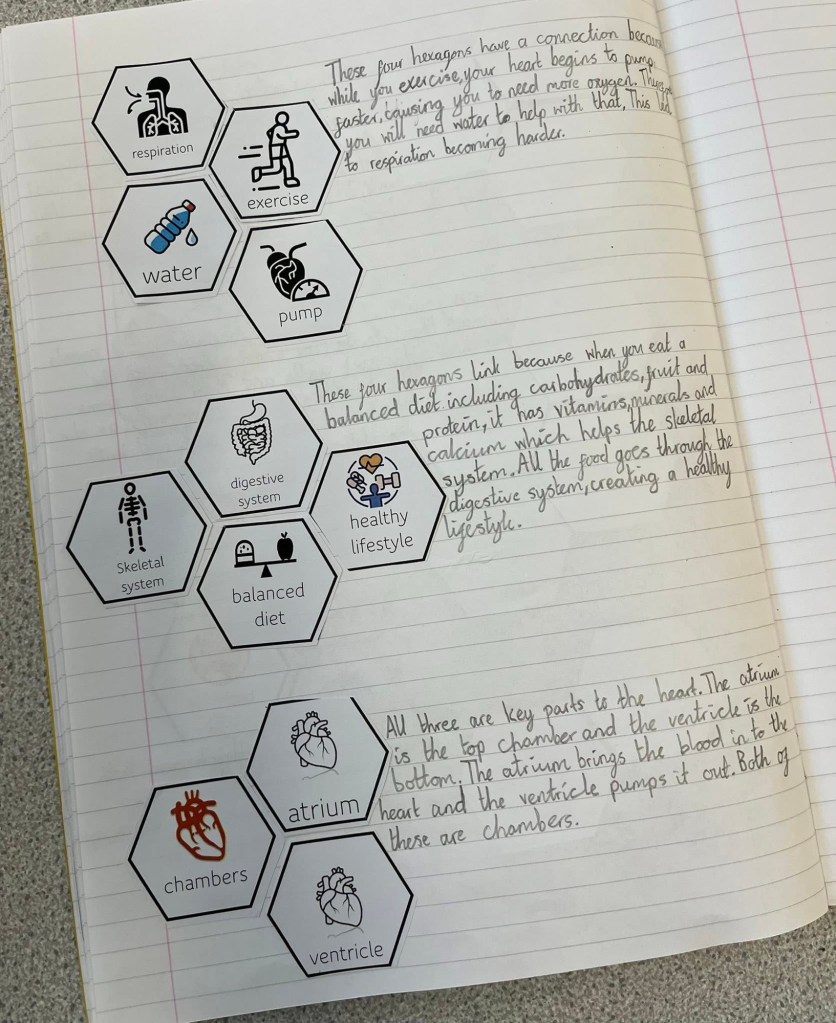

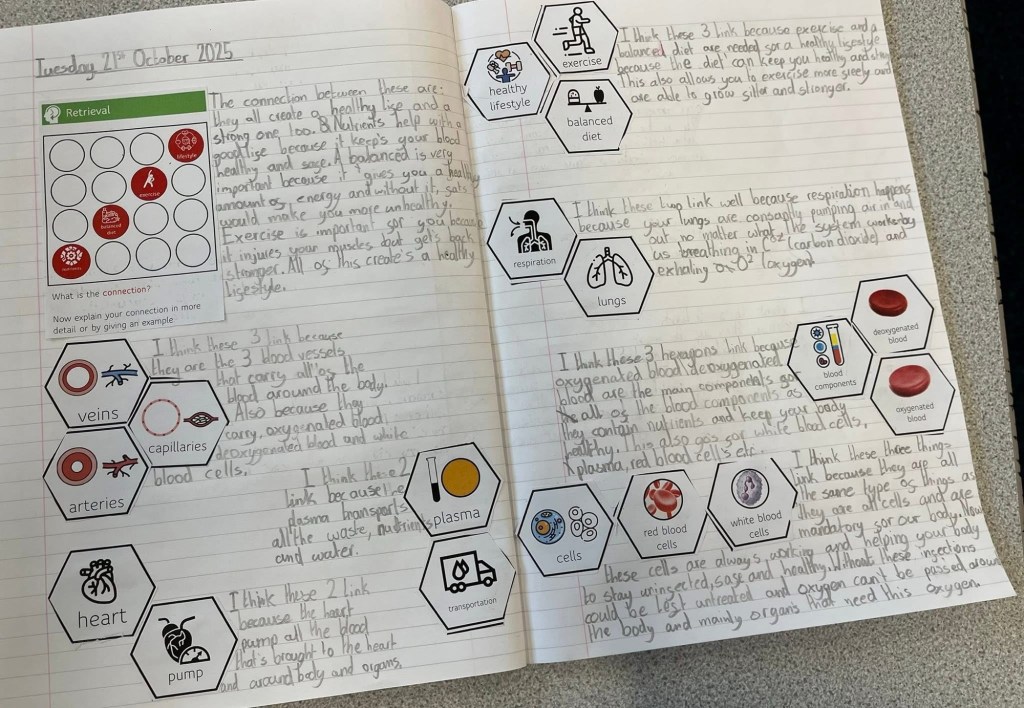

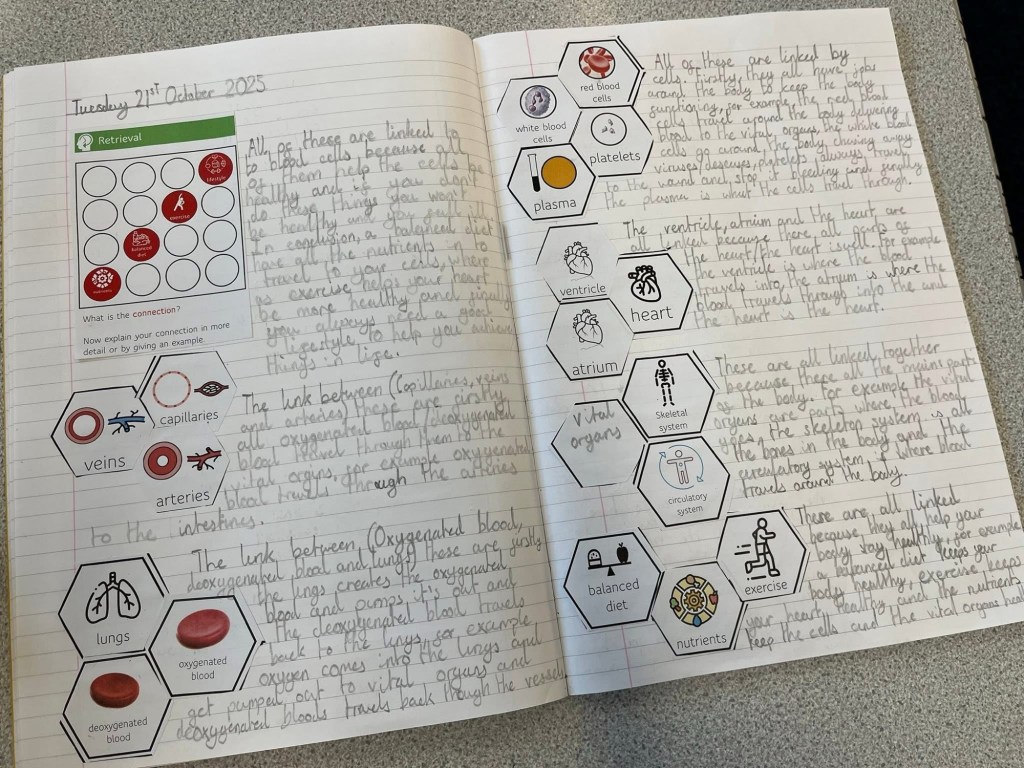

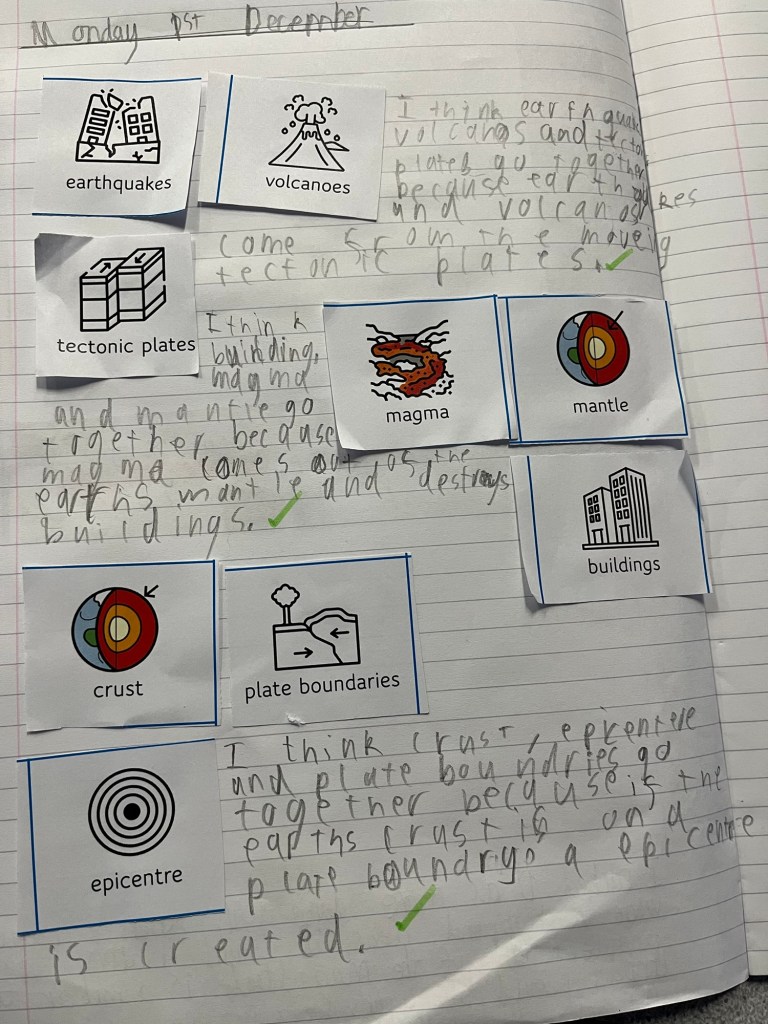

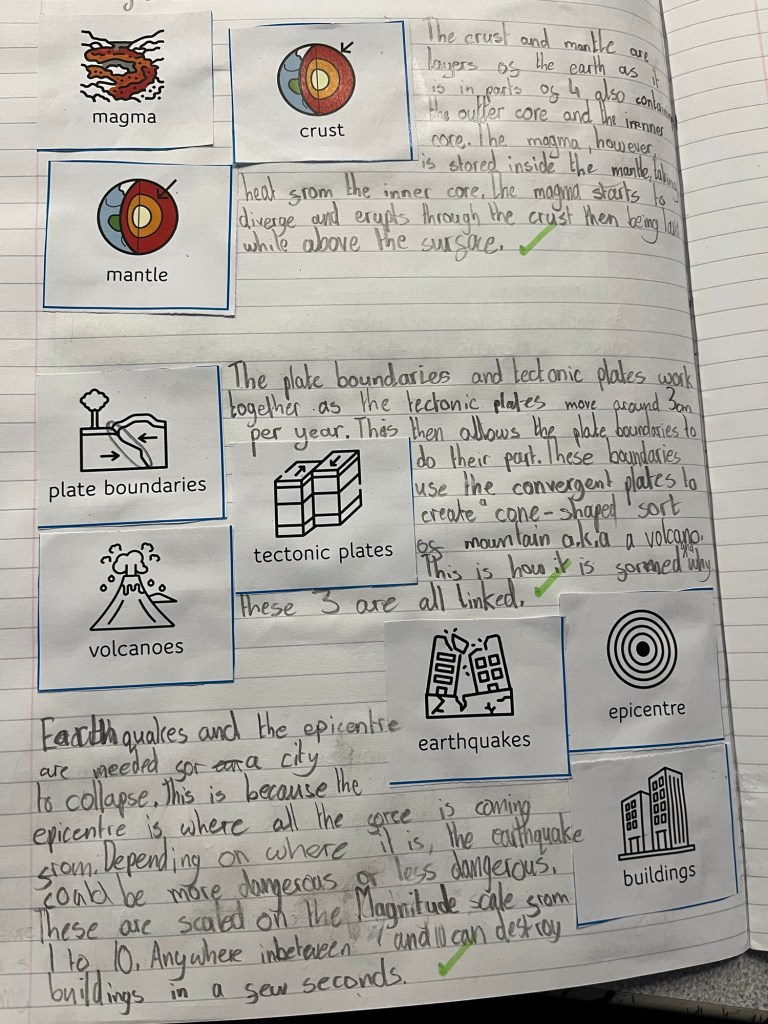

Hexagon mapping in science

This task is a popular one and is inspired by Pam Hook’s SOLO Taxonomy. It asks the children to show what they know through concept map connections (something I have written about previously here). It’s an authentic assessment opportunity because the children are able to demonstrate the structure of their knowledge in a visual way. You can see clearly whether their knowledge is fragmented or integrated, and you can see how shallow or deep their understanding is, based on their explanation.

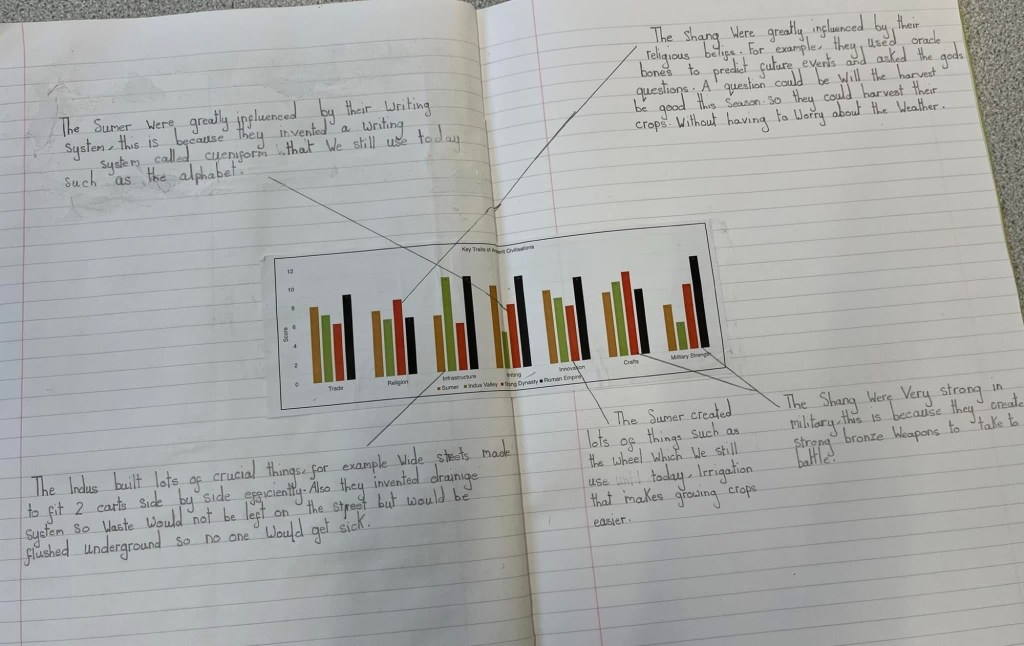

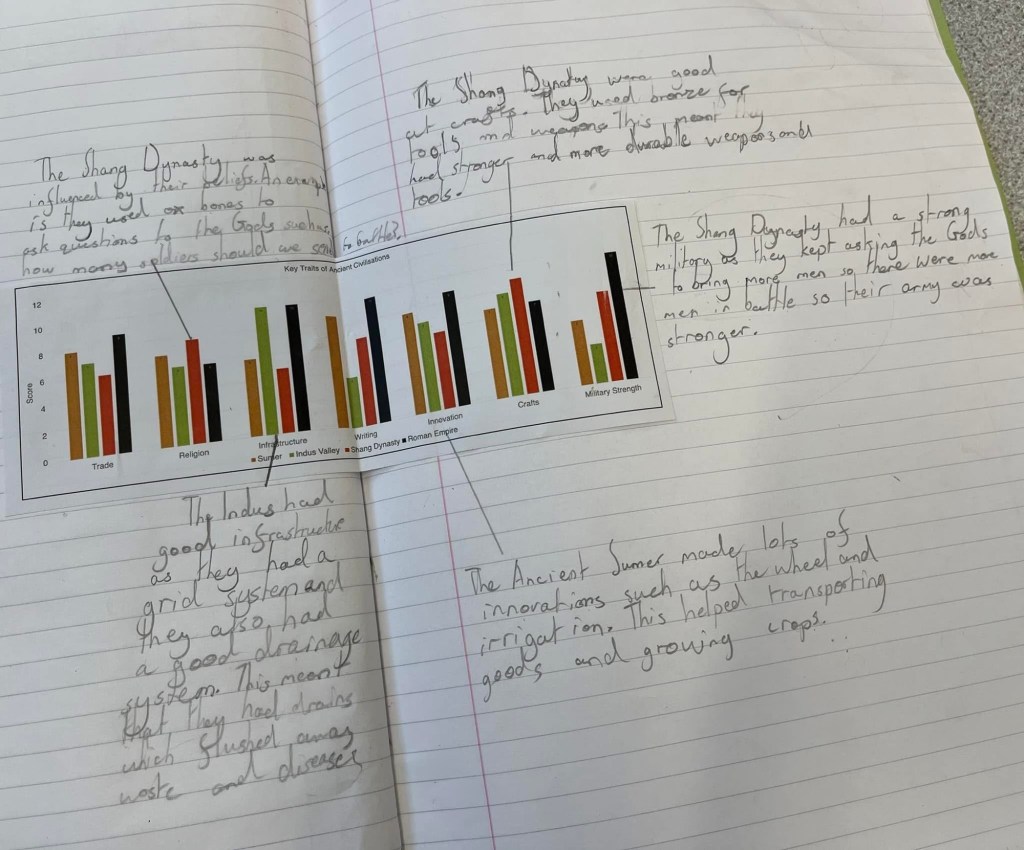

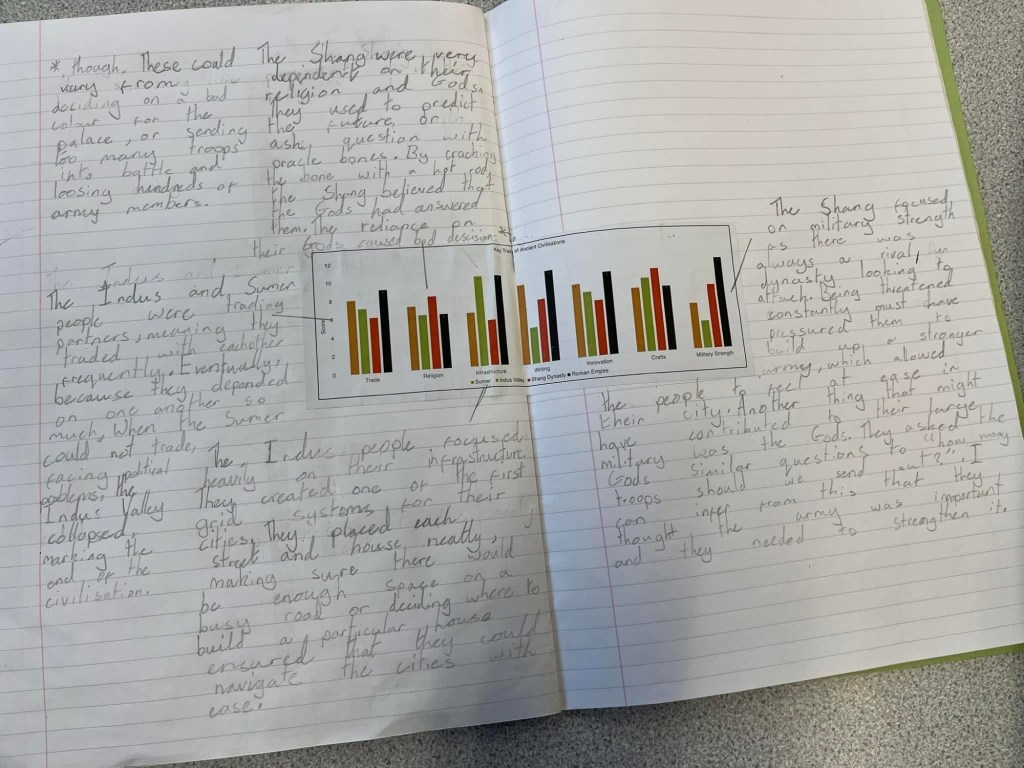

Civilisation characteristic graphs

When assessing the impact of ancient civilisations, in this task I created a graph based on the approximate interpretation of each civilisation such as their innovations, military strength and writing, among others. The children then explain why it shows a larger bar for military for the Romans in comparison to the Shang Dynasty around the graph. The children are connecting their understanding of the unit to the height of the bar and then they write an appropriate explanation; in a very similar way to the concept map. Again this helps us to infer the potential breadth and depth of knowledge without relying on extended writing because the children can simply bullet point.

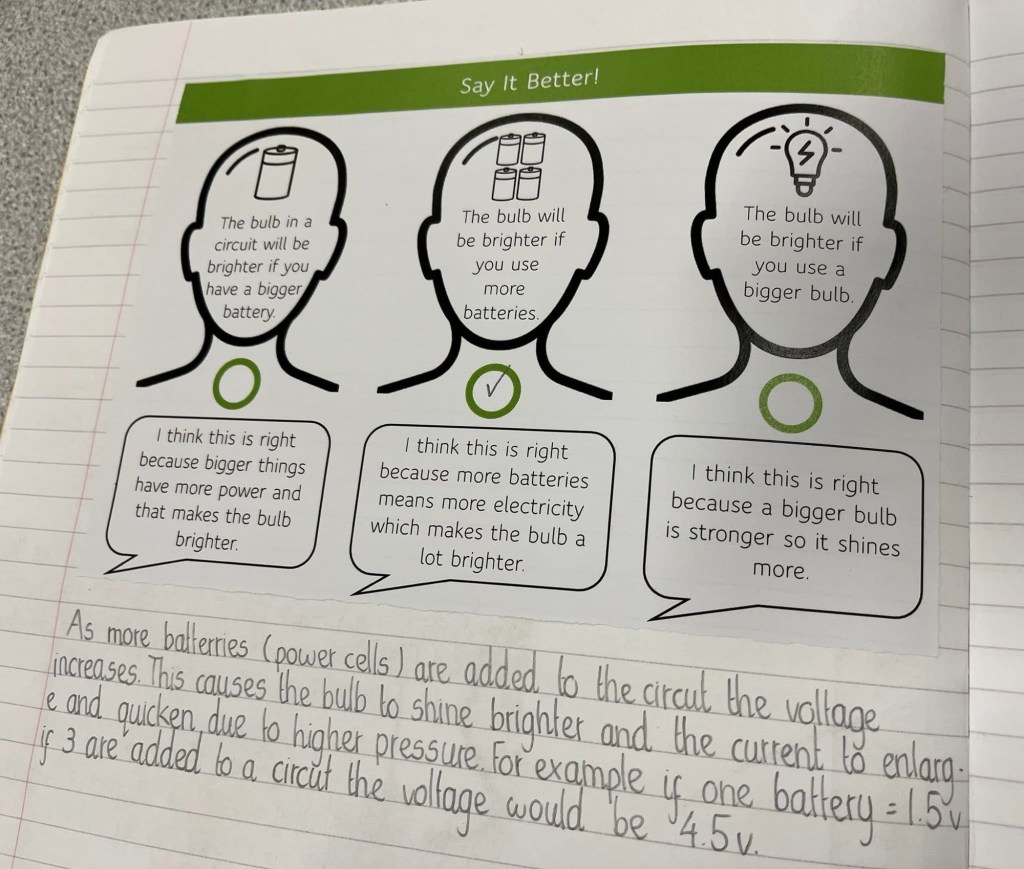

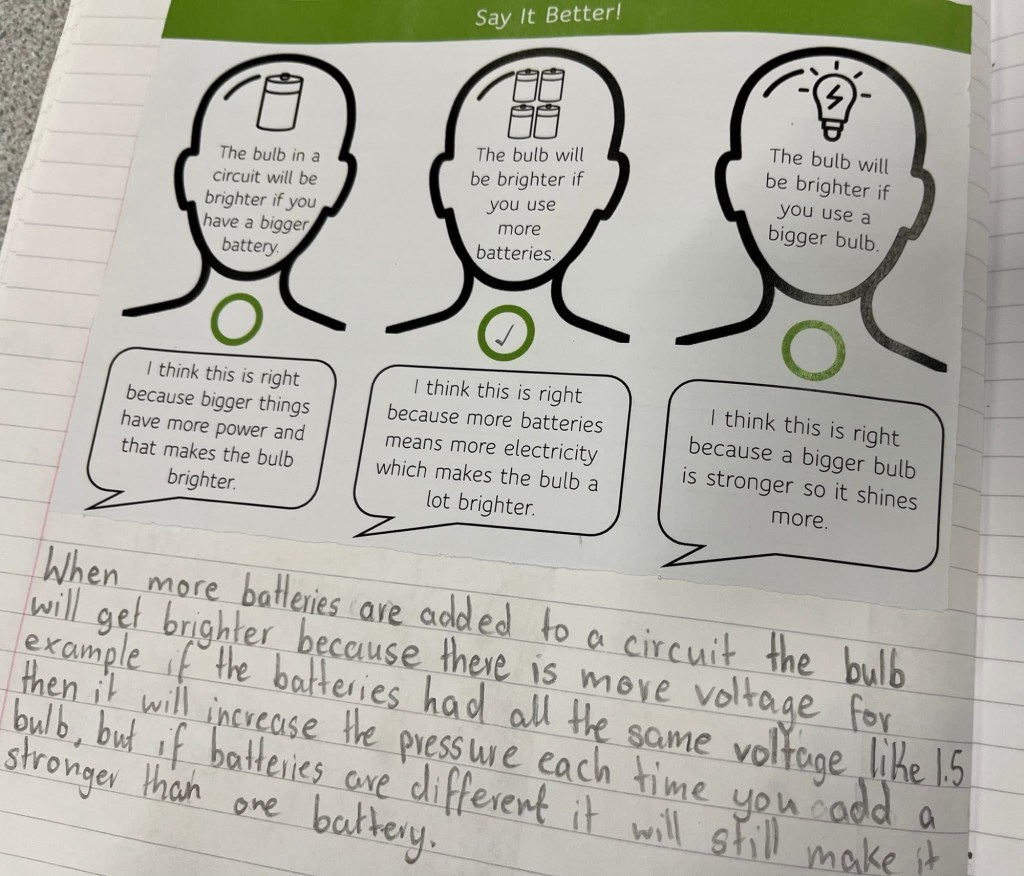

The “Three Heads” reasoning task

This task supports the building of more metacognitive talk. When children explain their judgement to each other using the three different points of thinking, it gives them a chance to properly discuss and challenge their understanding based on the three statements given. This time it was adapted slightly to include a ‘bad’ answer. This allowed the children to ‘Say It Better’ based on the WalkThru’s of the same name. This helps us see the quality of their reasoning rather than the neatness of their writing, it also gives children an explanation that they can hang their understanding on as opposed to trying to articulate their own in a ‘perfect’ way. When the children are discussing in pairs or trios I would circulate the room also building further mental inferences to identify how much or little the children understand.

Another follow up question I get asked regularly is about children who struggle to write at length or whose writing is not very legible. My answer is usually the same: you are the teacher, and you know best how to capture their thinking. Tools such as Showbie, SeeSaw and Book Creator offer great opportunities for children to verbally record responses in place of writing, particularly for those who find writing significantly difficult. However, I still encourage some writing, because scaffolds work best when they are gradually reduced rather than becoming permanent. I want high expectations for writing, yet we still need to recognise that, in extreme circumstances, writing can be a genuine barrier. Our job is to keep that barrier in view, and to build support that helps the children move towards longer, clearer writing over time. We have to remember in most secondary schools, children are expected to write, so we need to ensure they are ready for that next step.

All of these tasks are available in our Facebook Group – Primary Task Design.

Timeline of task design

It should be obvious that assessment is part of a curriculum loop, I have written about this in previous blog posts. After a sequence is taught, we should always look back at whether the content was correct, whether your instruction was appropriate, and whether tasks captured the curriculum intention. This cycle encourages us to be forward planning rather than any retrospective marking.

These tasks are just a small proportion of the types of task we use, and they aren’t always perfect. Often, we will use Socrative quizzes as an additional tool to infer understanding. However, they all serve as an assessment window because they reveal some aspect of the thinking or disciplinary structure, connections and misconceptions.

How Pupil Book Study strengthens assessment

As mentioned earlier, we use Alex Bedford’s Pupil Book Study process to support our assessments and as a curriculum evaluation tool because it:

– validates what the intended curriculum looks like in practice

– identifies points where substantive knowledge is secure or fragile

– highlights whether children have experienced enough disciplinary thinking

– reveals where our curriculum sequencing didn’t align with the intended progression

– shows whether tasks were accessible, manageable and appropriate enough.

In a lot of ways Pupil Book Study is a professional triangulation tool. It removes the temptation to rely on recorded outcomes alone, and it is not a monitoring tool. No one is being checked up on; it forms the purpose of professional dialogue between teachers and subject leads to identify improvements or refinements.

What we actually record

Outside of books, we should record only what actually supports the curriculum improvement. This includes:

– key insights from Pupil Book Study on a reflection sheet

– notes on any misconceptions that might need to be fed back into the next sequence

– any minor adjustments to the sequence’s substantive knowledge if it was overloaded in any way

– then finally curriculum decisions about balancing disciplinary and substantive knowledge

This form of recording has genuine purpose. It isn’t about recording names on a spreadsheet, it’s not producing long lists of attainment codes. Assessment is only purposeful if we do something with the data we collect. This form of assessment produces useful strategic information that strengthens the next cycle of planning.

Assessment becomes meaningful when it:

– rises naturally from the curriculum

– focuses on insight rather than compliance

– values teacher judgement as an interpretation rather than hard fact

– uses tasks that reveal children’s thinking rather than ability to tick the right box

– informs planning rather than justifying grades

This approach respects the nature of history, geography and science etc. It recognises that learning in these subjects is layered and cumulative. Whilst there is an increased exam based direction in secondary school, it is important that we respect how these subjects are designed in primary. They are designed to forge connections and show thinking in an increasingly visual way.

Final reflections

I always think of assessment bringing clarity rather than noise. For example, when my colleague suggested we do the ‘Only Connect’ assessment in geography recently, it showed really clearly that the majority of the class found it difficult to connect the word ‘epicentre’ to any of the other words, some were successful but not with the greatest clarity.

This clearly showed that there was something about how we introduced the word that didn’t land. So from that inference, we can refine the way we introduce it. Tasks that reveal thinking, combined with thoughtful Pupil Book Study and professional dialogue, give us the information that matters. Recording then becomes a purposeful act. We collect only what helps us refine the next sequence.

As Clare Sealy reminded us in our training, assessment is inference. Once we accept that, we can focus on triangulating evidence and designing tasks from the curriculum rather than forcing children into assessment events that tell us very little.

Thank you for reading, as always, I’m interested in your thoughts.

Karl (MRMICT)

A.I. was used purely to correct the grammar of this piece.

Leave a comment