https://www.impactedgroup.uk/resources/report-mind-the-engagement-gap

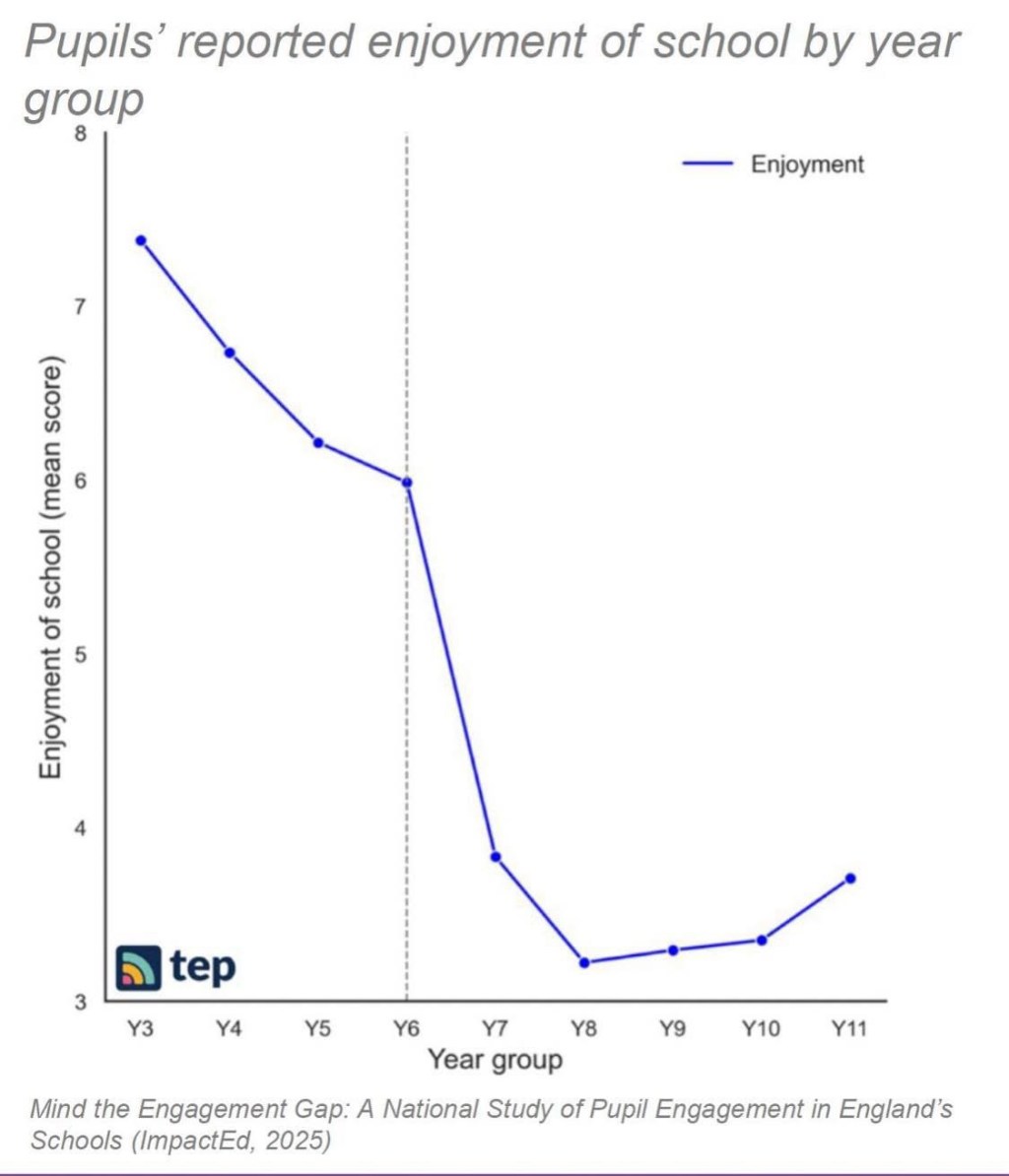

The Mind the Engagement Gap report by ImpactEd (linked above 👆) has been circulating this week; however, one graph is being shared and a narrative is being written; one that I think lacks nuance. It shows a steep drop in pupils’ enjoyment of school between Year 6 and Year 7. As a Year 6 teacher, that caught my eye. I agree it invites an important question and conversation for all of us who work across the primary/secondary bridge: what happens at that point of transition that makes such a visible difference to how children feel about school? Is it something we do in primary that needs to change to bridge that gap better? Is it something in Year 7 that needs to ensure a more gradual transition? There are answers on both sides of the drop.

What the data shows

ImpactEd’s national study draws on the responses of over 100,000 children across England. To be clear, it measures much more than “fun”. Engagement in this context includes a variety of factors: enjoyment, trust, safety, agency, and belonging. On each measure, primary pupils report higher levels than their secondary peers. The standout and ‘viral’ finding is that enjoyment drops from around six out of ten in Year 6 to below four in Year 7. The figures remain low through Key Stage 3 and only begin to rise again in Year 11. However, again this requires nuance. It is not about saying one school system is better than the other or that secondary schools have things wrong. It is an opportunity to think about what each phase does and how we can improve.

The data is consistent across backgrounds and regions, but the impact is sharper for children from disadvantaged families. The study also found that lower engagement strongly correlates with higher absence rates. The message here is clear: how children feel about school matters, and it matters early. This is not a new finding, and every teacher and headteacher knows this. There is, though, a shift in mentality among children and parents. Some might say it’s post-COVID; others would argue it has been brewing for longer. Ultimately, there are many factors and a huge number of possible answers. The answers aren’t, and shouldn’t be, political. I firmly believe that a school and its leaders know their context well enough to begin finding the answers within and to seek support when needed. There is the inevitable funding question, which is a huge issue; there is not enough money in our education system being channelled into the right places. But, as always, there are many voices competing. So, why might enjoyment dip so steeply?

Why enjoyment dips in Year 7

As I said before, there is no single factor that explains the pattern, but several influences are likely to intersect.

Change of environment: there is no denying that moving from one teacher and class to multiple subjects and larger spaces can be a huge shock and erode the sense of security and belonging that primary settings often nurture. However, I have seen examples where certain children thrive under this new system. A new teacher and new room each hour mean a fresh start and a new opportunity, along with greater variety. Is this something we need to emulate in primary? There are many advocates of the three-tier system for this reason.

Shift in relationships: children reported lower trust in their peers and adults after transition. This could suggest that relational safety plays a role in maintaining engagement. Again, there is an argument that more teachers mean navigating a greater number of relationships. However, as my wife is a secondary school teacher and form tutor, one of the things I hear continually is the safe space she has provided for so many in the drama department. Her work as a form tutor is transformative too, being that constant connection between pupils’ pastoral needs and their overall success. These roles cannot be overstated.

Increased demands: this one, in a way, speaks for itself, and as a Year 6 teacher, I feel that I drip-feed reminders that the demands on them in Year 7 will be greater. However, we also want the children to value the nowness of their education. We often tell them too much about what is coming next, which forces them to have one foot in the future. The new routines, homework expectations, and higher cognitive load may leave some children feeling less competent and less in control overall.

Loss of agency: there is no escaping the fact that, at certain points in your educational journey, learning is an act upon rather than an act with. For example, in Year 1 and Year 2 the children aren’t ‘involved’ or in control of their learning as such. It’s an expectation; they just have to, and teachers find incredibly creative and incentivising ways to encourage them. Perhaps if we imagine Year 7 in a similar way, it might help us rethink. They’ve gone from being the oldest in one phase to the youngest in another. They aren’t, but metaphorically they are ‘learning to read again’. So, while the study notes a drop in pupils’ sense of ownership over their learning, perhaps this is the inevitable ‘first steps again’ feeling, when learning can seem to be something done to them rather than with them, and motivation naturally wanes because this stage is hard.

Safety and wellbeing: this area is complex and deeply contextual.

Safety is experienced differently by every single child and shaped by both the school environment and wider social factors. The data shows that many pupils, particularly girls in Years 7–9, report feeling less safe in school than before. While I can’t speak from that personal experience, I am able to recognise and understand why it arises. The point here is not for individual teachers to speak for or from those perspectives, but to listen carefully and respond within our own settings. Every leader and teacher has a role in creating cultures where all children feel safe, heard, and valued, and where social conditions never undermine the motivation to learn. I believe this is where you find the ‘us-ness’ of your setting; what makes us a collective and what we hold as values.

The Pull of Instantly Reward Cannot Be Understated

There is also the wider cultural context to consider. The rise of platforms such as TikTok, YouTube Shorts, and Fortnite marathons has created a powerful instant-reward loop that shapes how children experience attention, satisfaction, and enjoyment. Jonathan Haidt’s work on The Anxious Generation argues that constant digital stimulation can narrow focus and heighten sensitivity to short bursts of novelty, making sustained engagement in slower, more effortful learning feel less rewarding by comparison.

In this sense, the enjoyment drop around Year 7 may not be purely about transition between schools, but also about children adjusting to a world that offers endless, frictionless stimulation outside it. This is why phone free schools and parents engaging meaningfully in the limitation of the children’s digital lives are more and more important that ever.

What we can do in Year 6

As I have said repeatedly, this is not a story of blame or deficit. It is a call to strengthen continuity. As primary teachers, we are well placed to help children cross the bridge with a greater sense of confidence and strength as learners. A few principles stand out.

Build agency before they leave – Encourage meaningful choice in tasks, routines, and reflection. When children experience autonomy in Year 6, they carry that confidence into secondary contexts. The key here is that it needs to be reflective of the expectations in secondary. I continually think that we need to model, in a small sense, the environment and expectations they will experience in secondary but make it our own and ensure it doesn’t move them to have one foot in the next too soon.

Rehearse independence in safe conditions – We can still model subject changes such as moving to new rooms and new teachers. Last year, I taught computing in both Year 6 classes, and our headteacher taught RE in both classes, so it was a window into different styles and expectations. We can encourage more independent study with different homework expectations and styles, and use feedback cycles that mirror secondary structures, but with the support that is still close at hand, which is what makes primary different. It demystifies what lies ahead.

Prioritise relational preparation – The human side of transition often matters more than the logistical. My wife and I often talk about how shared projects with secondary schools increase the sense of belonging and soften the experience. We have a local Shakespeare project which builds connection between schools as pupils experience workshops from the drama and dance departments. Do we build this in strategically and thoughtfully? This is a positive I often see in middle schools and academy trusts. Informal Q&A sessions are key. The head of our local secondary comes in and speaks to the Year 6s after the open evening and gives them a more intimate and informal opportunity to ask questions.

Keep language and routines consistent – This is something I think we can do on both sides of the border. Where possible, we can align key terminology and expectations between schools. Maybe it’s a familiar approach to marking or to classroom routines. Again, it needs to respect both contexts, but it can soften the shock of change.

How secondaries can help

Secondary colleagues face a complex challenge too. The first term of Year 7 is crowded with adjustment. The data suggests that the greatest gains may come not from curriculum overhaul but from time spent nurturing relationships, explaining systems clearly, and listening closely to early feedback.

A shared responsibility

The dip in enjoyment between Year 6 and Year 7 should not be read as inevitable, nor should it be seen as something that belongs to one particular setting’s responsibility. It is not a reflection on one school, any curriculum model, or even the education system as a whole. It is something that, in England, is significant, but it is a reminder that engagement is relational and developmental. Children thrive when they feel safe, are known, and are trusted. That feeling is cultivated through the very small everyday choices teachers make: the structure of a task, the tone of feedback, the invitation to think more independently, gradually.

If we design transitions with the same care we give to curriculum sequencing, the line on that graph might start to look very different. Perhaps the goal is not to prevent all dips in motivation, but to make sure they are brief, recoverable, and surrounded by adults who know how to steady the bridge.

Questions for the next transition discussion

How do our current transition activities build agency as well as familiarity?

What indicators, if any, could we use in Year 6 to identify children at risk of disengagement?

How might secondary colleagues use early pupil voice to track and respond to changes in enjoyment, safety, and trust?

Karl (MRMICT)

Leave a comment