Every so often, a comment online stops me in my tracks, not because it’s offensive, but because it intrigues me and says something important about how we see our profession or about the state of education in general.

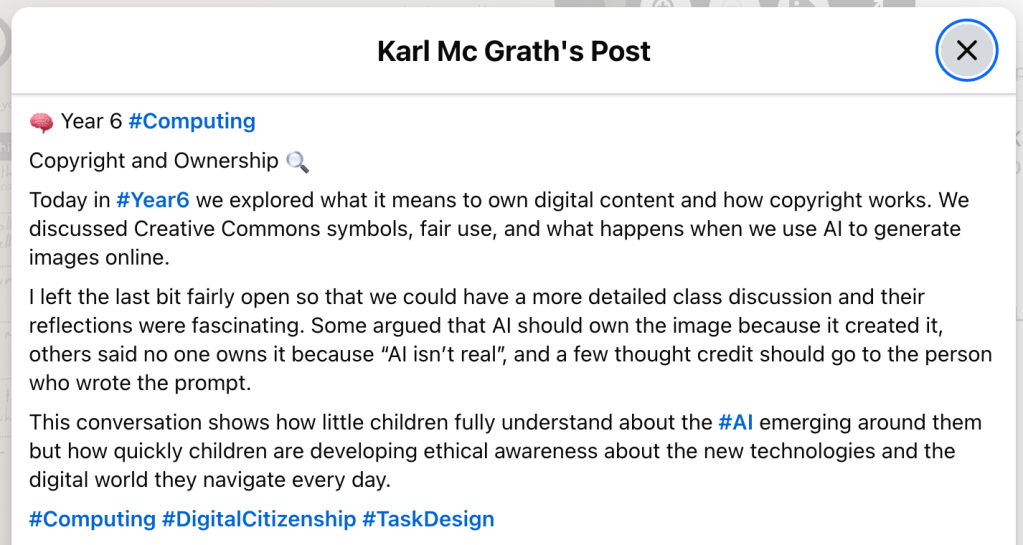

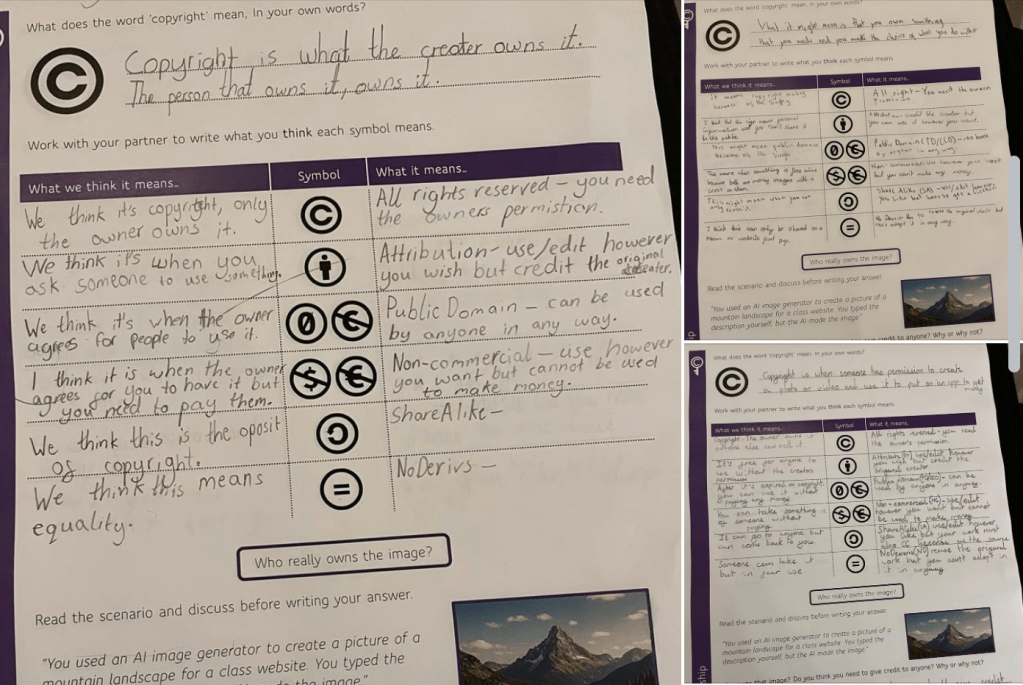

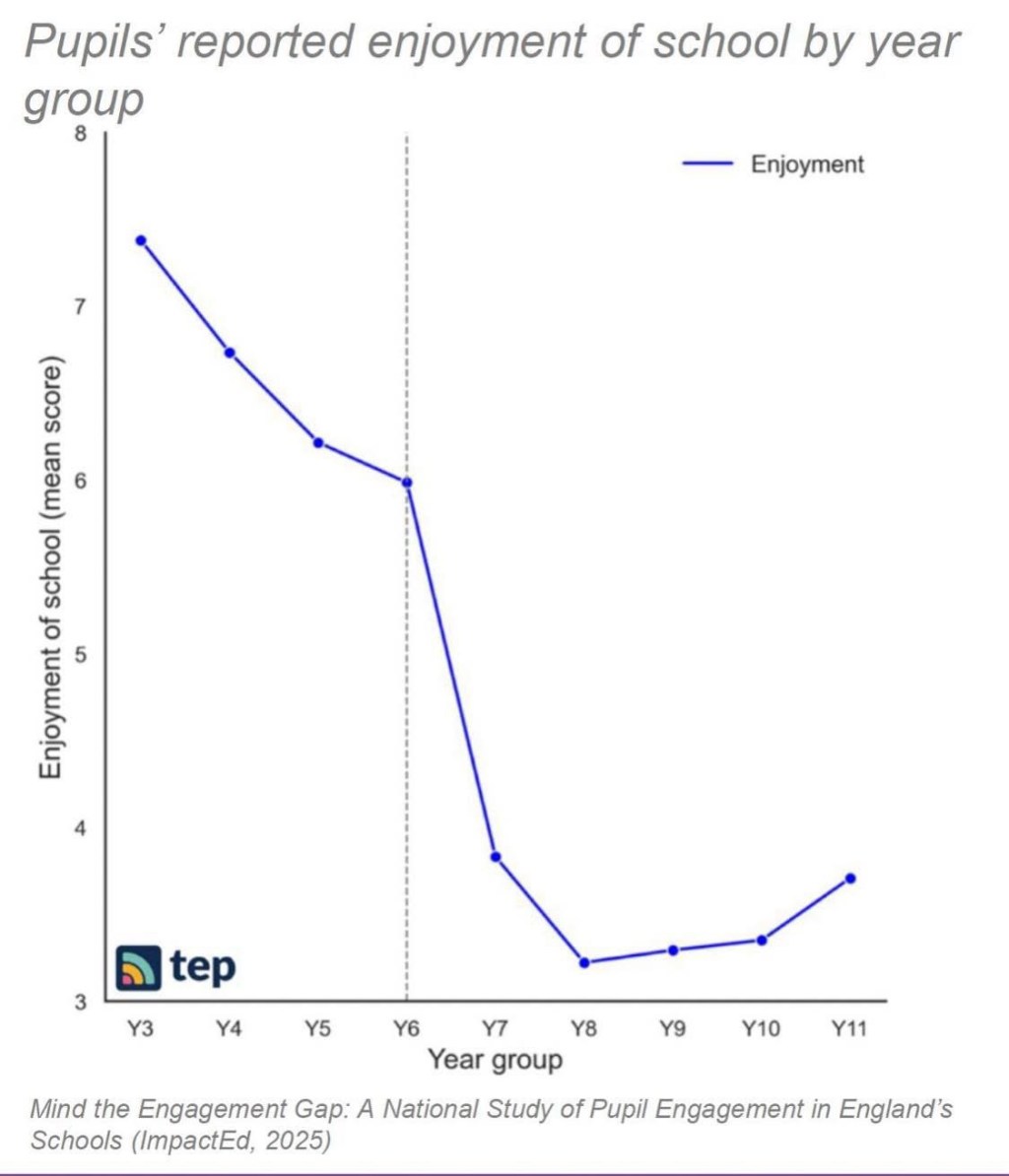

Last week, I shared a Year 6 computing task exploring copyright and ownership in the age of AI. The children were asked to discuss who owns an AI-generated image: the creator of the prompt, the AI tool itself, or no one at all. The responses were thoughtful, nuanced, and far beyond what most adults might expect and it opened p an interesting discussion in class that helped me see their very shallow understanding of AI but how deeply they are immersed in it. Yet, there was one response to my post described the lesson as an example of the primary curriculum being “1mm deep and 1km wide” perhaps suggesting that the primary computing lacks the kind of rigour found in secondary. They also suggested that they would rather have children that could follow instructions and answer questions that complete the kind of work I was sharing.

Now it is one comment, many others were supportive and if I’m honest I share my work and the children’s work fairly unabashedly. Why? I find the capacity for our children to think deeply is incredible, and they always continue to surprise me. Additionally, It was a fair comment to debate, but it reminded me of a deeper issue and one that shows there is still a huge divide in understanding on both sides of the KS2 line.

The false hierarchy of depth

The assumption that the primary curriculum is shallow is not new. It’s often rooted in a misunderstanding of what depth means at different phases of education. It is always something that eve primary practitioners share, wrongly, I would argue. When the curriculum review was announced there were cries from every corner of the primary phase to remove sections of the incredibly wide and shallow primary curriculum. However, in primary, depth is conceptual rather than technical. It is clear to me that primary involves helping children understand the world through accessible but precise knowledge, laying the groundwork for later complicated abstraction.

So for example, a Year 6 child discussing digital authorship is not trying to match a GCSE computing spec. They’re developing initial disciplinary habits: reasoning ethically, using accurate vocabulary, and making connections across contexts differing contexts. Those habits then become the roots from which more complex disciplinary thinking grows.

By contrast, secondary computing, and indeed all secondary subjects, move towards formalisation and specialisation. My wife is an incredibly talented secondary performing arts teacher specialising in dance and I honestly could not make it clear just how complicated, academic and challenging GCSE dance is, it is not at all linked to any primary curriculum areas that will slowly build up the required knowledge base. So here, the depth in secondary is technical: in computing it involves precision, algorithms, programming, and systematic problem-solving. Both are obviously rigorous, but in different ways.

Where the idea comes from

The distinction between conceptual depth (in primary) and technical depth (in secondary and beyond) comes from many overlapping strands of curriculum theory, research and cognitive science rather than a single specific source. My own curriculum research leads me back to a few key people.

Counsell’s work on curriculum as a narrative argues that in primary, curriculum design focuses on coherence, story, and meaning-making. She argues that children at this stage are busy building conceptual schema and mental frameworks for understanding ideas like cause, change, and evidence. This is necessary before they can handle the more technical apparatus of subjects.

“Conceptual depth in the early curriculum lies in the richness of meaning and connection, not in the quantity of abstract content.” (Counsell, 2020, “Taking Curriculum Seriously”, Impact)

Cognitive Development and Abstraction

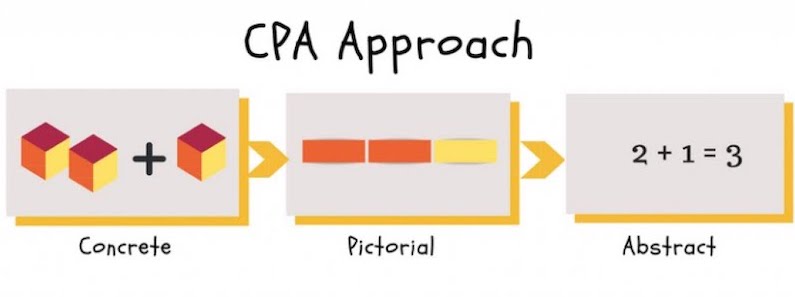

This distinction between conceptual and abstract draws from Bruner (1960) and Vygotsky (1978), who share that children’s capacity for abstraction develops through representation and scaffolding. In primary, depth comes from building robust conceptual representations of how things relate (for example, what a ‘civilisation’ is, or how forces interact), rather than mastering procedural or technical fluency that depends on later cognitive maturity.

This is also another reason why a huge amount of my task design work focuses on allowing children to make connections and challenge their understanding; something that also connects deeply to generative learning. Fiorella and Mayer (2015) define generative learning as the process of actively constructing meaning by integrating new information with existing knowledge. In other words, children learn best when they generate understanding through reasoning, explaining, or representing ideas, rather than simply receiving and regurgitating them.

Designing tasks that require children to link, compare, justify, or explain creates the perfect conditions for this kind of learning. Whether through hexagon connections, “true–maybe–false” reasoning, or sequencing tasks that reveal deeper conceptual relationships, the focus is always on thinking with knowledge, not simply recalling it. This is where conceptual depth is built: in the cognitive work of transforming what is known into new understanding.

- Bruner’s “spiral curriculum” model emphasises revisiting key ideas at increasing levels of abstraction, explaining why primary focuses on conceptual depth.

- Vygotsky’s “zone of proximal development” supports the idea that conceptual understanding precedes and supports later technical proficiency.

Ofsted and the “Curriculum as Progress Model”

I use Ofsted hesitantly, however, their was lots that was good in its Education Inspection Framework (2019) and its subsequent curriculum reviews (particularly the Research Review Series), In them they explicitly refer to “depth of understanding” in primary as being about conceptual connections and schema-building rather than developing technical expertise.

“Younger pupils need to grasp the key concepts that underpin the discipline; such as evidence, cause, and change, through substantive content that is meaningful to them.” (Ofsted, History Research Review, 2021)

Willingham and Hirsch on Foundational Knowledge

It would be ridiculous to look at curriculum discourse without referencing cognitive scientist Daniel Willingham and curriculum theorist E.D. Hirsch. Both of these educational juggernauts argue that conceptual understanding depends on secure foundational knowledge. Primary curriculum and teaching is then clearly about building depth of meaning within concrete contexts, again, conceptual rather than technical depth.

This distinction is research-based, drawing on curriculum theory, developmental psychology, and cognitive science rather than a single source.

The narrowing illusion

It is common for primary to be criticised for being too broad, however, secondary is also misrepresented, unfairly, as narrowing children’s opportunities to favour exam outcomes, particularly for GCSEs. This is obviously as equally reductive. Secondary teachers operate within significant pressures of accountability, specification content, and qualification frameworks. Their challenge is not a lack of ambition but a constraint of structure.

To me secondary is about proficiency. It is a place for children to develop the ‘expertise’ that is required in the secondary subjects, some of which that children have had little opportunity to experience in primary such as dance and to some extent a quality design and technology or computing education.

Just as I would fight back against the claim that primary is “1mm deep,” I would never dismiss secondary as narrowing of options in as simply a lack of creativity. In both cases, the problem lies not in intent, but in the conditions in which teachers work.

Two phases, one journey

The Facebook exchange stayed with me because it clearly reflects a pattern I’ve seen repeatedly: each phase too often assumes what the other does, without seeing it firsthand. Many secondary colleagues have limited opportunity to observe the complexity of primary sequencing, just as many primary teachers rarely see how conceptual progression unfolds through Key Stage 3. I am also acutely aware that secondary schools receive children from a very differing range of settings, which is also perhaps why they may perceive primary standards in a particular way, which is another reason why we should not dismiss each others work.

The result is ultimately gap in understanding, not in quality.

Primary teachers think in breadth, designing curriculum sequences that build cumulative knowledge and disciplinary thinking. Secondary teachers think in depth, refining precision, technique, and conceptual fluency. When those two approaches align, children experience education as a coherent continuum. When they don’t, it feels like a disjointed jump.

Misconceptions about research and best practice

Another misconception is that one phase is more “evidence-informed” than the other. I see as much careful curriculum thinking in primary staff-rooms as I do in secondary departments. Both draw on cognitive science, EEF guidance, and disciplinary research. The difference is often one of framing and resource, not professionalism.

We sometimes use the same language—curriculum, retrieval, task design—but mean subtly different things depending on phase and context. That difference can either be a barrier or a bridge, depending on how willing we are to learn from one another.

Towards shared professional learning

We could do more to close this gap.

- Joint moderation and curriculum discussions between Year 6 and Year 7 teachers could strengthen continuity.

- Cross-phase CPD on disciplinary thinking would highlight how reasoning develops over time.

- Task exemplars that show what rigour looks like in each phase would help replace assumption with understanding.

If we are serious about progression, we need shared professional dialogue rather than defensive comparison.

Conclusion

In primary, we design for thinking – helping children organise and manipulate knowledge conceptually. In secondary, we design for precision – helping learners apply that knowledge technically within the conventions of each discipline. Across both, accessibility ensures that every child can enter the learning, sequencing ensures knowledge builds securely, and knowledge itself remains the anchor that gives both phases coherence.

When task design keeps these principles central, the transition between conceptual and technical learning feels purposeful rather than abrupt. It reminds us that the difference between phases is not a divide in rigour but a shift in focus, from making meaning to mastering method.

That Facebook comment could easily have sparked an argument. Instead, it became a reminder that both phases face misconceptions that undermine their complexity. The truth is simple: the primary curriculum is not shallow, and the secondary curriculum is not narrow. Both are designed with intent, shaped by context, and delivered by teachers who care deeply about getting it right.

As always I am open to conversations, criticisms and comments.

Karl (MRMICT)

Leave a comment