This blog post started, as many things do these days, with a scroll through social media whilst drinking my Sunday morning coffee.

A post popped up in my Instagram feed: “Create effective Ofsted-friendly classroom displays.” I couldn’t quite believe that this post was being shared, let alone by one of the largest educational publishers in the UK.

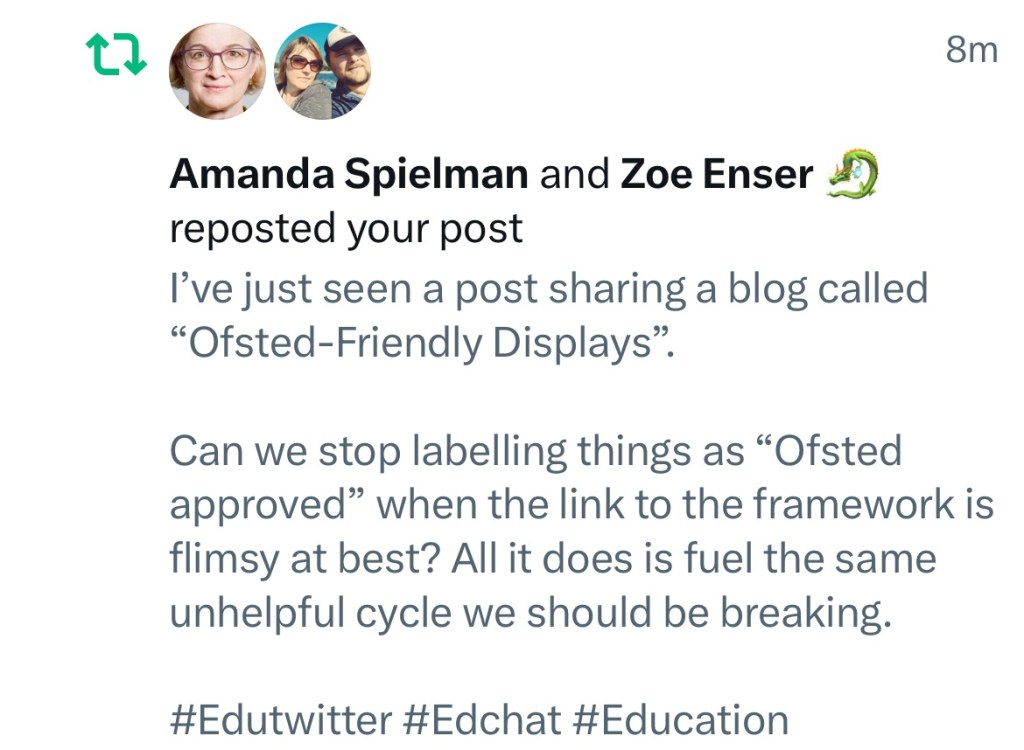

I decided to share an X post, purely because it is literal ‘Ofsted baiting’ – essentially dangling a claim, “Do this and Ofsted will be pleased”, to attract attention, even when there’s no explicit requirement in the inspection framework. It trades on teachers’ anxiety about inspections and workload, often encouraging them to invest time and effort in things that, whilst giving the impression of quality, have no direct bearing on inspection judgments or the children’s learning.

I have read the blog post, and the word ‘MAY’ is doing just as much heavy lifting as “Ofsted-approved”. The link to the inspection framework is, frankly, flimsy at best. I was reassured when others such as Zoe Esner, weighed in, noting that whether or not you have a display has no bearing on inspection outcomes. It struck a chord, not because I dislike displays, I don’t mind them, but because the way we talk about them is often more exhausting than the act of putting them up.

I said to a colleague of mine recently how divisive a discussion on displays really is, and I genuinely find it incredibly hard to understand. To me, displays are akin to the colour we choose to paint the walls. There are slightly more nauseating colours, but it’s literally just a colour.

If you walk into ten different schools, you’ll likely see ten different approaches. Some classrooms have vibrant walls brimming with children’s work, key vocabulary, and topic-themed borders. Others favour “working walls”, where the content evolves with the journey of the learning. In my own teaching, I’ve found that a whiteboard or a roll of whiteboard tape and a blank surface can be the most adaptable display of all. They’re quick to change, they flex to the lesson, and they don’t involve hours of lamination or perfectly angled staples.

I have taught in some incredibly ‘noisy’ classrooms, visually noisy, that is. Words on walls, angled ceilings, children’s work – it really can be overwhelming. Additionally, I see regular posts on Facebook groups asking for display ideas.

I fully understand the experience of being a brand new teacher, with the motivation of putting your stamp on the class or creating calming reading corners as a space to allow children to regulate. There are spaces within your classroom that absolutely deserve your attention, but you are the adult and it is ultimately your decision. However, we should not be doing something because we think, or are told, that Ofsted want it.

So, what do headteachers make of all this?

The National Association of Head Teachers (NAHT) doesn’t issue any directives about displays, but it does talk often about workload and the importance of focusing on what genuinely impacts the learning of the children. They argue repeatedly that in a climate where every additional task competes with planning, assessment, and, frankly, the ability to go home at a reasonable time, it’s little wonder that leaders are cautious about mandating elaborate wall-space expectations. Of course, school leaders are entitled to mandate displays – many do. I suppose my belief is that if you’re a leader reading this, ask yourself why you’re insisting your teachers or support staff spend so much precious time on displays.

Ofsted’s own position is also more muted than the “Ofsted-friendly” description that some in the profession would have us believe. The School Inspection Handbook makes no stipulation that classrooms must have specific displays. As mentioned in the blog, it states: “Inspectors may look at the environment” – yes – but their focus is on whether it supports an ambitious, coherently planned curriculum and fosters an inclusive, calm atmosphere. In other words, a wall-sized topic display covered in laminated, hand-cut lettering with false ivy and hessian backing is not, in itself, a ticket to a glowing inspection report. Neither Amanda Spielman nor Martyn Oliver have ever announced that a certain style of display will curry favour with inspectors. And yet, the idea persists. Ironically, Amanda herself reposted my tweet.

What does the research say?

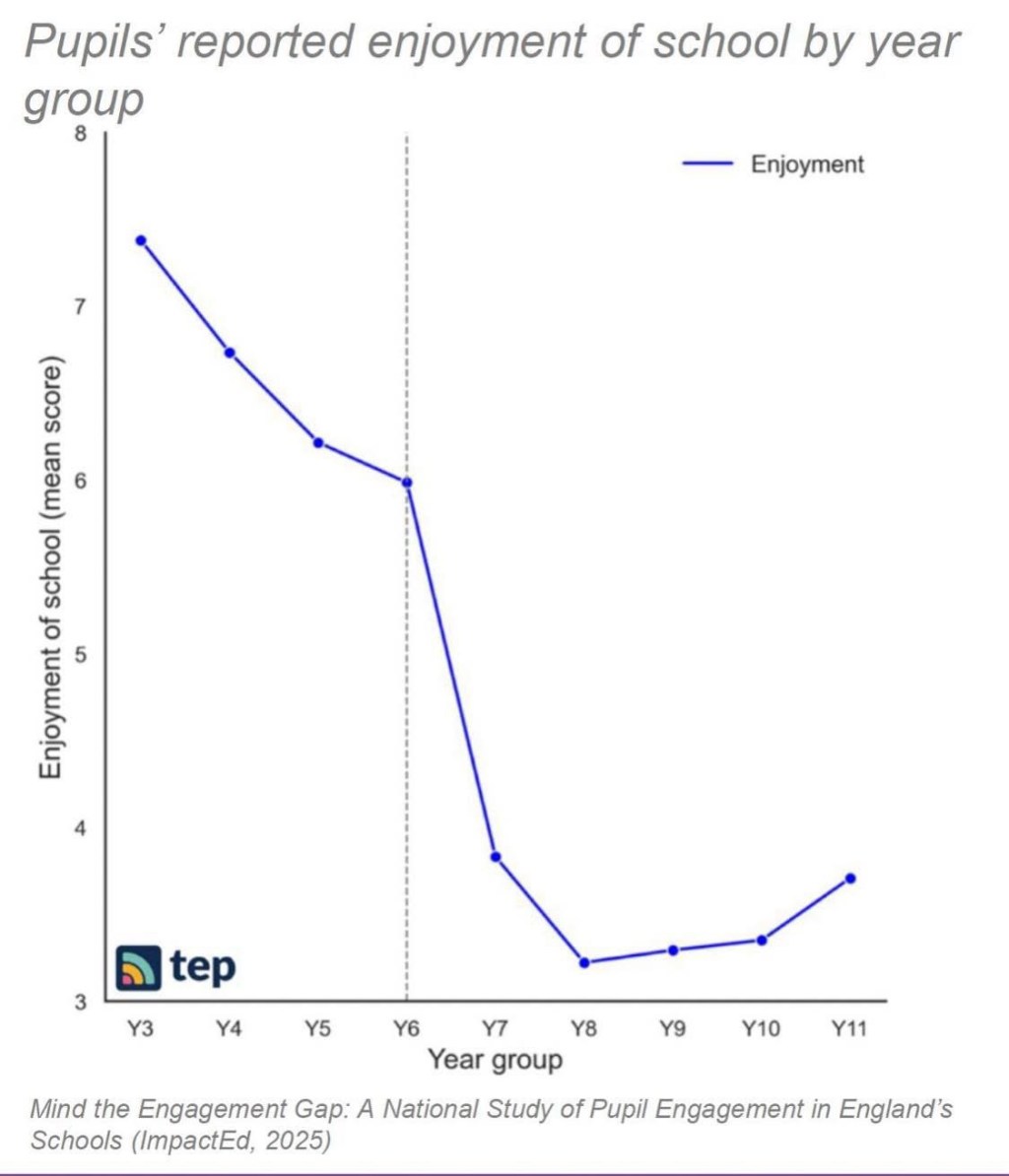

The research paints a nuanced picture. Many studies show that highly decorated classrooms can distract younger children, drawing attention away from the task at hand. Eye-tracking research can identify further that displays can significantly affect where children focus, with even greater impact on those with autism spectrum disorder.

Cognitive load theory reminds us that if information on a wall isn’t clearly linked to what’s being taught, it can become noise rather than support. It’s always important to offer the counterargument. I found the Clever Classrooms study, led by Professor Peter Barrett, whilst doing a little further research, and it states that well-balanced, thoughtfully designed environments, including displays, can account for a meaningful slice of variation that some pupils need to progress over a year. It’s also worth noting that displays featuring children’s own work can promote belonging and nurture pride, making the classroom feel like it’s theirs as much as the teacher’s.

So, where does that leave us?

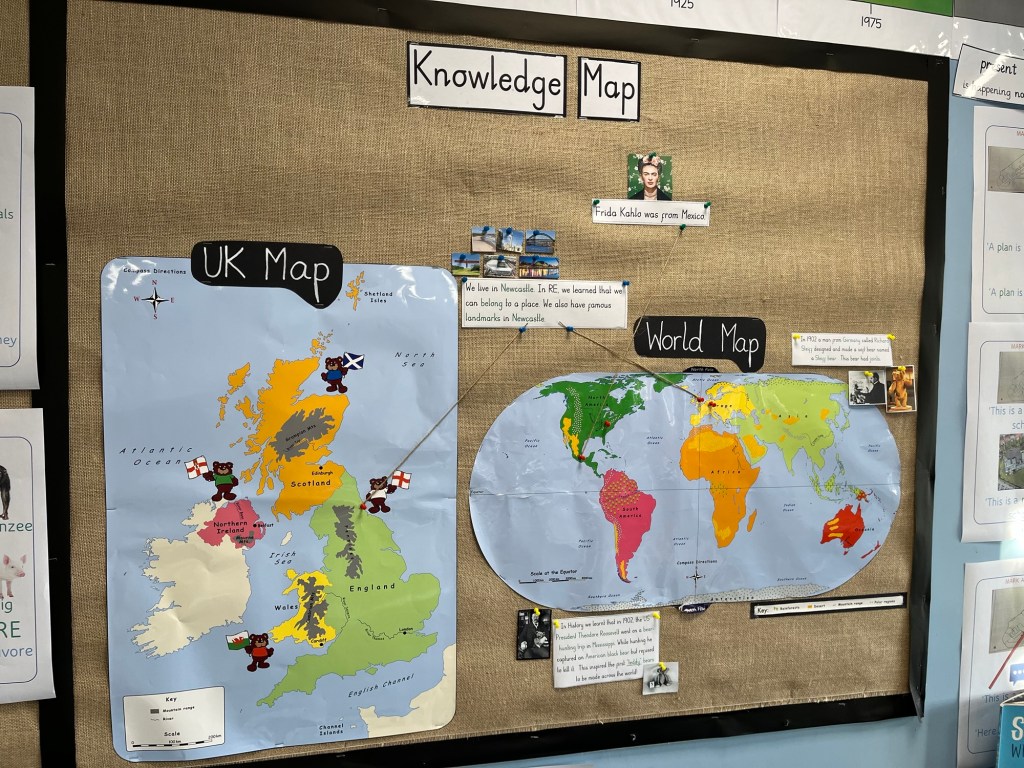

For me, it comes down to intentionality and sustainability. I’m not about to suggest that we ban displays or strip walls bare. I’m also not about to pour evenings and weekends into crafting intricate boards that look wonderful but serve little day-to-day purpose. My favourite displays are the ones that change with the learning, if that change can happen within the lesson – even better. In an ideal world, I would like a whiteboard with an outline of the UK zoomed out from Europe and the world, ready to be annotated with the geography, history, or wider curriculum. I also use English and Maths whiteboards to model calculations, which grow as concepts develop. In our school, each classroom has a knowledge map, inspired by Andrew Percival at Stanley Road Primary, where a world map becomes a living record of the vocabulary and ideas we’re exploring. I often walk towards it to show where we’re talking about and its relation to other countries during the lesson.

Classroom displays can and should enrich the learning environment, but they don’t need to drain our time or energy to do so. The key is to make them work for the children and for us, to design with a purpose that extends beyond any perceived inspection mythology, and to remember that the most effective display might just be the one that’s easiest to update.

As always, comments and criticism are welcome.

Karl (MRMICT)

Leave a comment