Mary Myatt recently posed a simple yet intriguing question:

“Do quality curriculum resources matter?”

Her answer – “Of course they do!” – is one I wholeheartedly agree with.

I’ve seen Mary speak on this very topic, and she makes the case abundantly clear: children don’t need cartoon caricatures or A.I.-generated sources; they need the real deal. However, I’d go further: quality resources are only as effective as the tasks we build around them. A resource might be rich with potential, but without a coherent learning sequence or narrative, coupled with thoughtful, well-designed tasks, it risks becoming something surface-level and low-value – a worksheet, a filler, or a quick win.

The first challenge is selecting great resources. But then we need to start thinking. I will always argue that if we, the teachers, are thinking deeply about how we design tasks, then we can be confident that children will think deeply too. Tasks that provoke curiosity and take children into the heart of a subject don’t happen by accident. This is where curriculum-driven task design matters.

Mary offered a helpful set of questions to help evaluate curriculum resources:

On a scale of 1–10, how likely are these resources to:

💭 Make my pupils think?

🧐 Provoke curiosity?

🚀 Take my pupils deeply into the topic?

These questions resonate because they cut through the noise of mass-produced, one-size-fits-all resources that too often dominate classrooms. The risk of over-relying on pre-packaged materials is that the deep thinking, both for teacher and child, is done elsewhere. The curriculum becomes diluted, the tasks become mechanical, and curiosity fades. We don’t want our children moving aimlessly from step A to B. We want a resource that sparks discussion, creates narrative, and builds a grander picture.

Task design and sequencing is about slowly peeling away layers and giving children opportunities to connect the dots and make meaning — not just across a single lesson, but over weeks, and even years, to forge a strong schema.

From Resource to Task

Let’s take Mary’s example of Greek mythology, the story of Demeter and Persephone. A mass-produced worksheet might ask children to complete a cloze paragraph or a simple matching exercise. But does that task really spark engagement with the myth? Does it help them explore its themes of life, death, and renewal? Probably not.

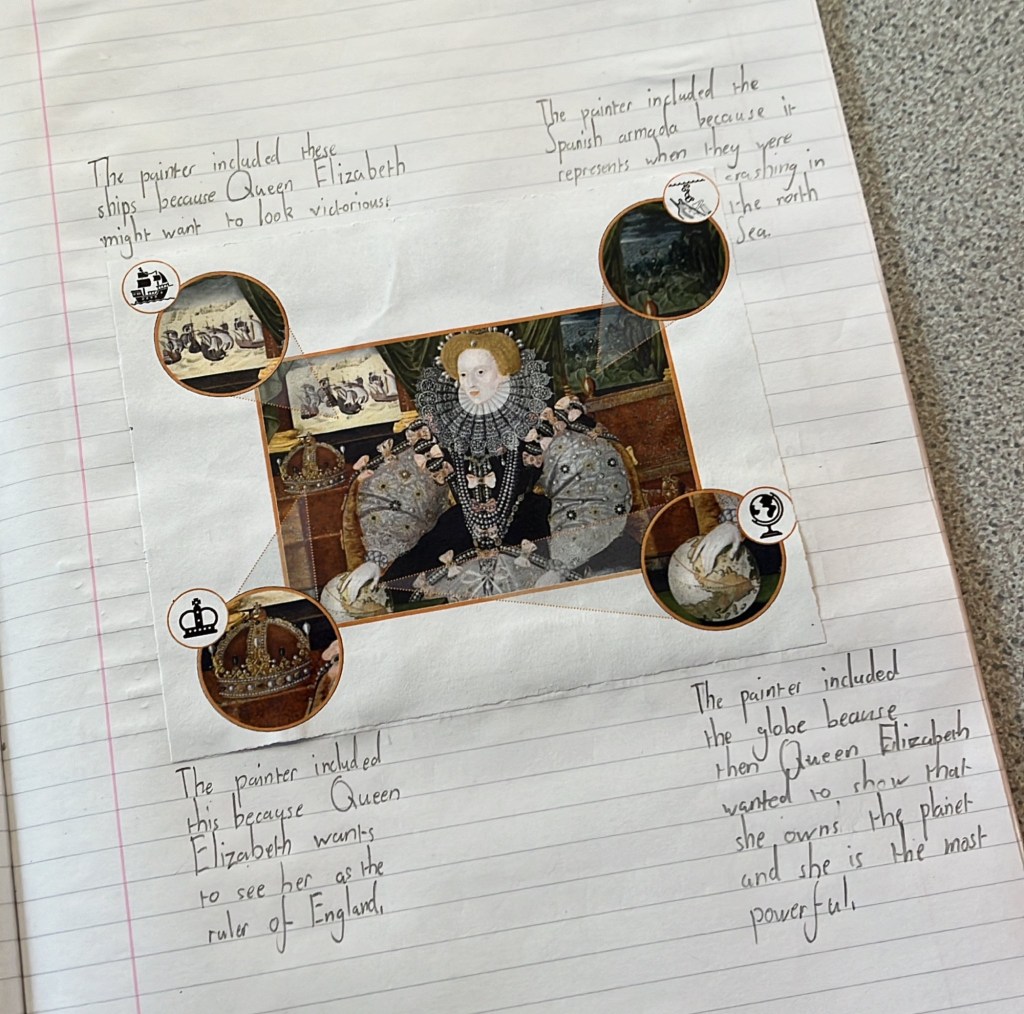

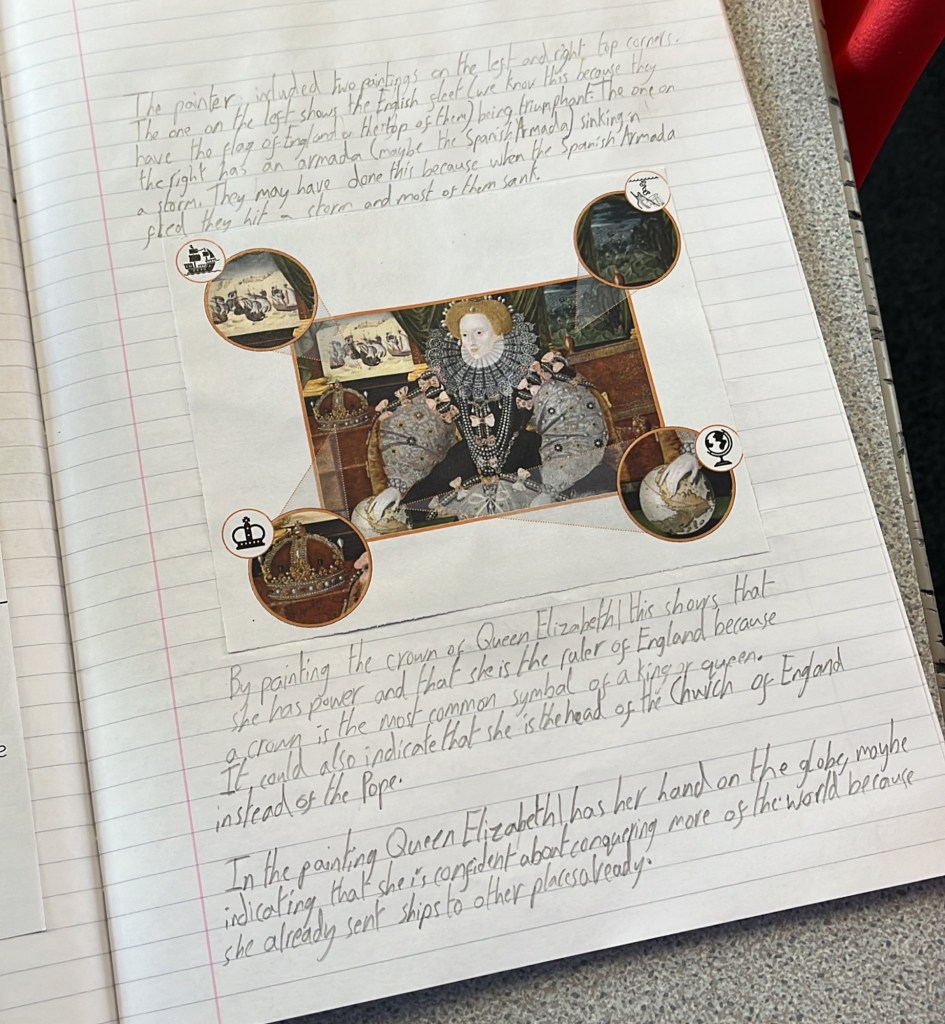

Now imagine designing a task that uses an authentic source, such as the artefact Mary references from the British Museum. Rather than asking pupils to recall facts, the task could invite them to interrogate the image. One approach I use is the ‘zoom in’ method, shared by Tom Mole on X (formerly Twitter). It’s a brilliant way to draw children’s attention to a specific aspect of a source or artefact. It reduces cognitive load while focusing their observation; unlike the well-worn “I see, I notice, I wonder” or ‘Inference Square’ which, in some cases, can quickly descend into a list of disconnected observations.

The zoom-in method isn’t appropriate for every source, but when it fits, the results are powerful. In the examples below, children engaged with the symbolism in the Armada Portrait of Queen Elizabeth I. Their interpretations show a genuine engagement with power, authority, and historical narrative, far beyond “label the crown”.

What these tasks show is how children, given the right structure and stimulus, can do far more than ‘answer comprehension questions’. They can question, interpret, connect, and infer.

We might ask questions such as:

🔹 What story might this image be telling?

🔹 Is there anything missing from this story?

🔹 Is there anything this image doesn’t tell us, that we still need to know?

🔹 Why might this myth or painting have mattered to the people who created it? How do you know?

If you’re inclined to go this deep you could possibly ask:

🔹 How do the images and symbols in this piece of art connect to the wider ideas of seasons, empire, or change?

Suddenly, the task has moved far beyond recall. It makes children think. It provokes curiosity. It deepens understanding.

Why Task Design Matters

The point of curriculum task design is to bridge the richness of curriculum knowledge with meaningful cognitive work. When done well, it does more than check if children have understood something; it makes them understand by grappling with it. It pushes them to make connections and form conclusions based on knowledge and reasoning – not shallow social media opinions or TikTok-era shortcuts that are presented as facts.

Mass-produced resources often remove the nuance and narrative from learning. They’re designed for speed, not depth. I understand why they exist, teachers are time-poor, and I agree there’s a certain irony here, given many people use the task models I’ve shared. But I stand by my approach: open-ended thinking structures that can be made once, used lots.

The goal is not to tag tasks onto a scheme that has already been planned at arms length. The goal is to build tasks that emerge from the curriculum itself, from the concepts, narratives, and disciplinary thinking that our own talented subject leads want children to explore. Not what a ‘Big Box’ education publisher says is “fun”.

Questions We Should Be Asking Ourselves

So perhaps we can extend Mary’s scale and apply it to tasks as well:

1️⃣ On a scale of 1–10, how likely is this task to require children to do any thinking?

2️⃣ On a scale of 1–10, how likely is this task to help children see connections between ideas or stories?

3️⃣ On a scale of 1–10, how likely is this task to take children beyond surface-level recall and understanding?

These aren’t just rhetorical questions. They’re practical filters. They help us avoid the trap of low-level busywork or ‘decorative’ activities that occupy time but add little substance.

Final Thought

Mary is right – quality curriculum resources absolutely matter. But I would add: quality task design is the bridge that transforms a great resource into great learning.

When we lean on authentic sources, build meaningful narratives, and shape purposeful tasks within these narratives, we create lessons that are not only knowledge-rich but deeply human, and profoundly empowering for the children we teach.

If you have already done so, consider joining our Primary Task Design community here:

All educators and leaders welcome, the idea is simple: to create a space where teachers can discuss, critique and share positively their task designs or curriculum thinking.

As always, comments or criticisms welcome!

Karl (MRMICT)

Leave a comment