I get asked about retrieval a lot and it is an aspect of teaching and learning I will champion time and time again. There is power in revisiting prior knowledge, strengthening memory, and embedding understanding all of which are fundamental to how children learn. However, for me, retrieval is far more than a quick whiteboard flash or a set of discussion questions at the start of a lesson. If we really want to value retrieval, we need to design retrieval tasks that move beyond regurgitation and into the realm of disciplinary thinking. Retrieval tasks should be adaptable and I do share a range of templates regularly, however, the questions and approach need to interact with the discipline.

Download Our – Retrieval Task Templates

You can also find a range of our tasks and approaches here in the Primary Task Design Facebook Group: https://www.facebook.com/share/g/1C2yL77gTp/?mibextid=wwXIfr

What is retrieval? What does the Research Say?

There is a vast amount of research in the field of retrieval by cognitive scientists like Robert Bjork, John Dunlosky, and Barak Rosenshine. All of which, have repeatedly reinforced that retrieval practice strengthens memory and recall, making learning more robust over time. Bjork’s theory of desirable difficulties suggests that retrieval is most effective when it challenges learners, pushing them to reconstruct knowledge rather than simply recognise or recall it. We do a lot of this already at school and we have made significant progress in many areas, for example teaching in discrete subjects rather than grouping them in topics. Additionally, in maths we are already used to varying the presentation of questions and tasks to increase difficulty to desired level. Yet, we still don’t do this automatically in subjects such as geography or history, however, this forms a firm part of our task design approach.

Kate Jones, who has written extensively on retrieval, emphasises that it should be a deliberate and sustained process embedded within a learning sequence. Retrieval is not just about assessment, it should be designed in ways that deepen understanding and make subtle connections across curriculum disciplines. I still shudder and gasp when people mention pre and post assessments, I have written on this already, but the idea of assessing children at the beginning of the unit to determine what they don’t know is a fallacy. Too often, retrieval tasks become low-level recall exercises that don’t require children to do much more than pull a fact from memory. While fact retrieval has its place, we need to ensure that retrieval tasks reflect the complexity of the subject discipline itself, as well as respecting the discipline.

Retrieval Is More Than Just a Quiz

A common misconception is that retrieval is synonymous with quick-fire questioning, whiteboard work or low-stakes quizzing. While quizzes can be useful and this is often the case, retrieval should go beyond simple recall of facts or notes from last lesson and instead it should engage children in a meaningful cognitive effort. Here’s how I think we can elevate retrieval practice:

Using Retrieval to Strengthen Connections

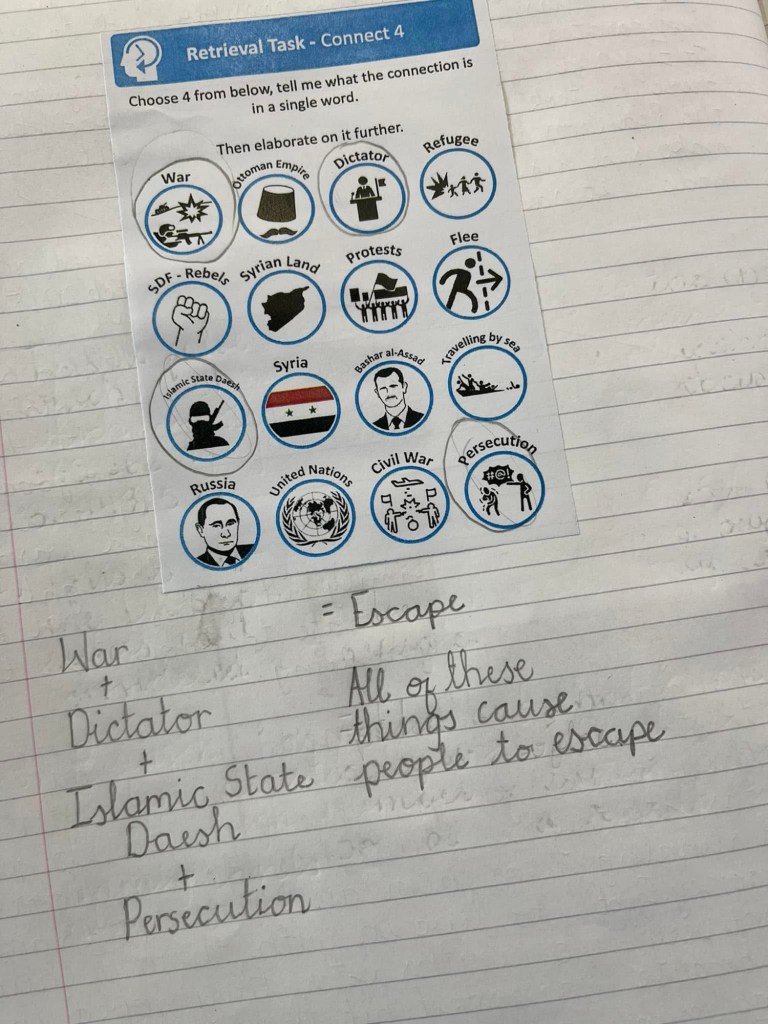

One of the biggest pitfalls in retrieval task design is treating knowledge as isolated facts rather than interconnected ideas. If retrieval is only ever used to test single pieces of information (e.g., “What is the capital of Syria?”), we miss the opportunity to strengthen the connections between knowledge. Instead, we should structure retrieval tasks that require children to link prior knowledge to new learning.

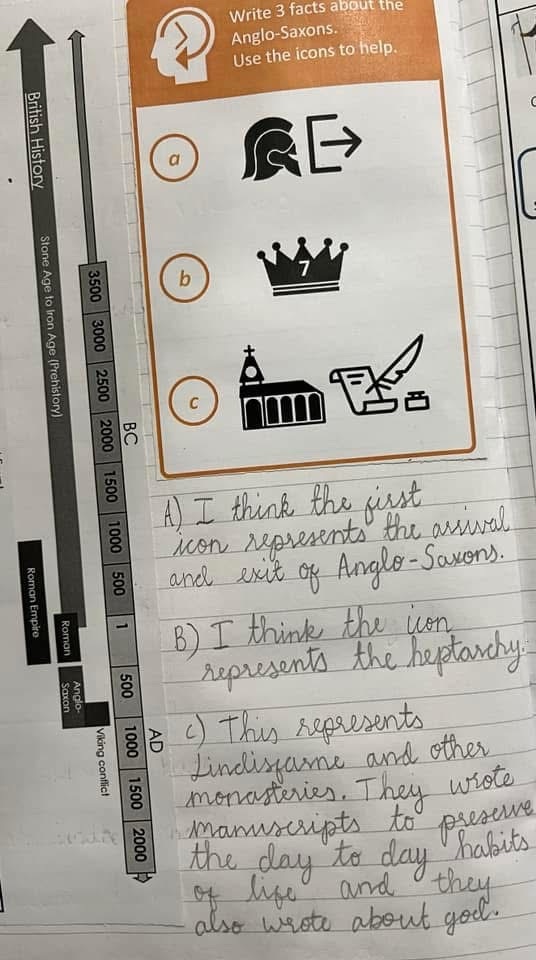

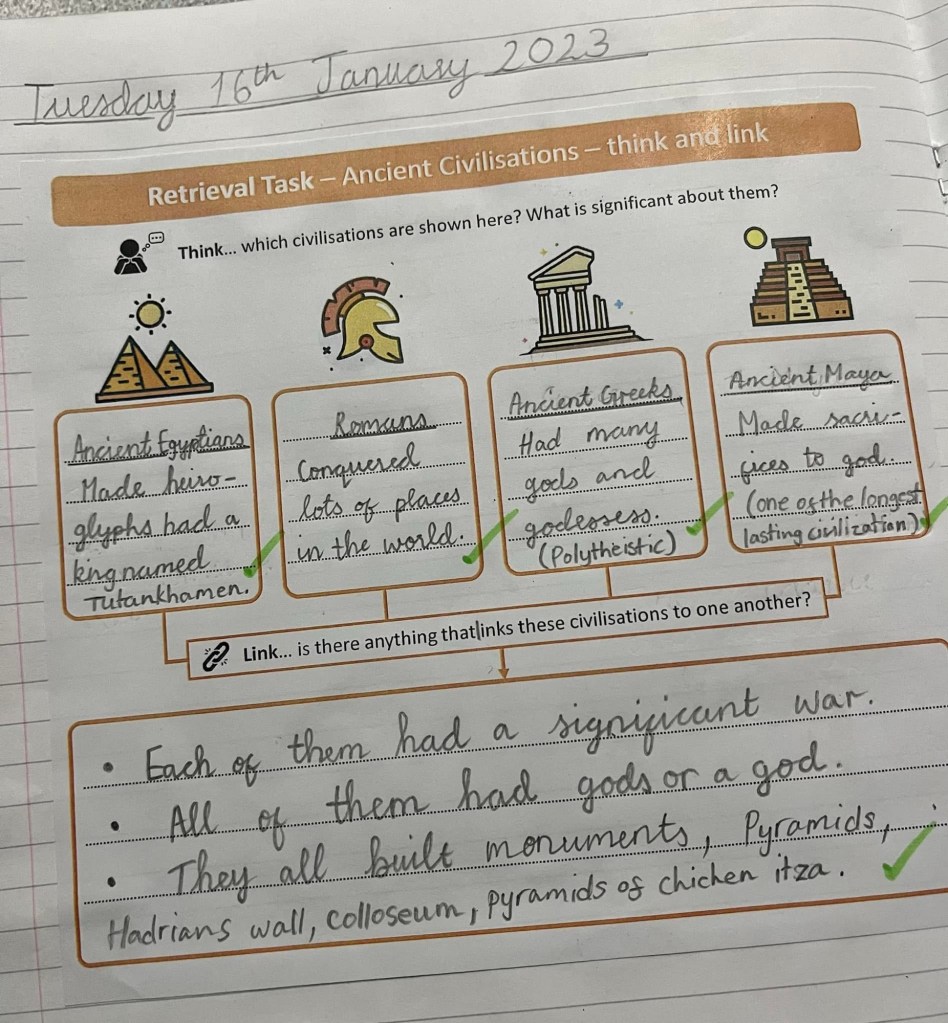

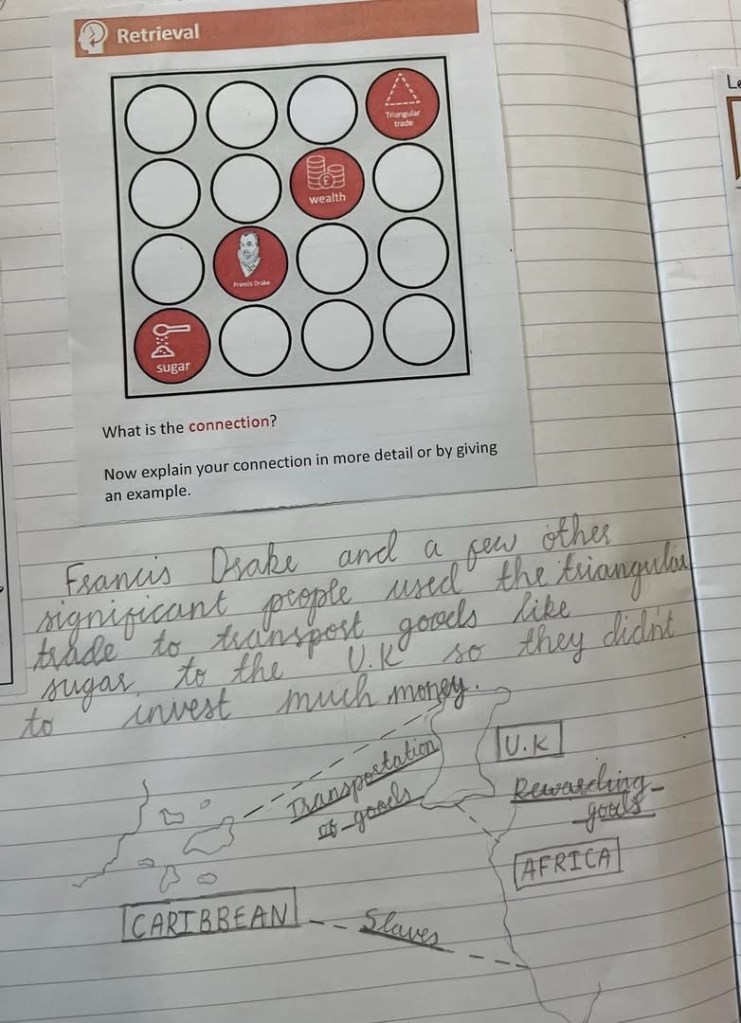

In history, instead of asking children to recall a single fact like, or asking basic things like, “What do you remember about the Anglo-Saxons?”, aim to:

Use icons or anchors to illicit what the children remember. Whether this is correct or not it allows you to truly diagnose any misconceptions.

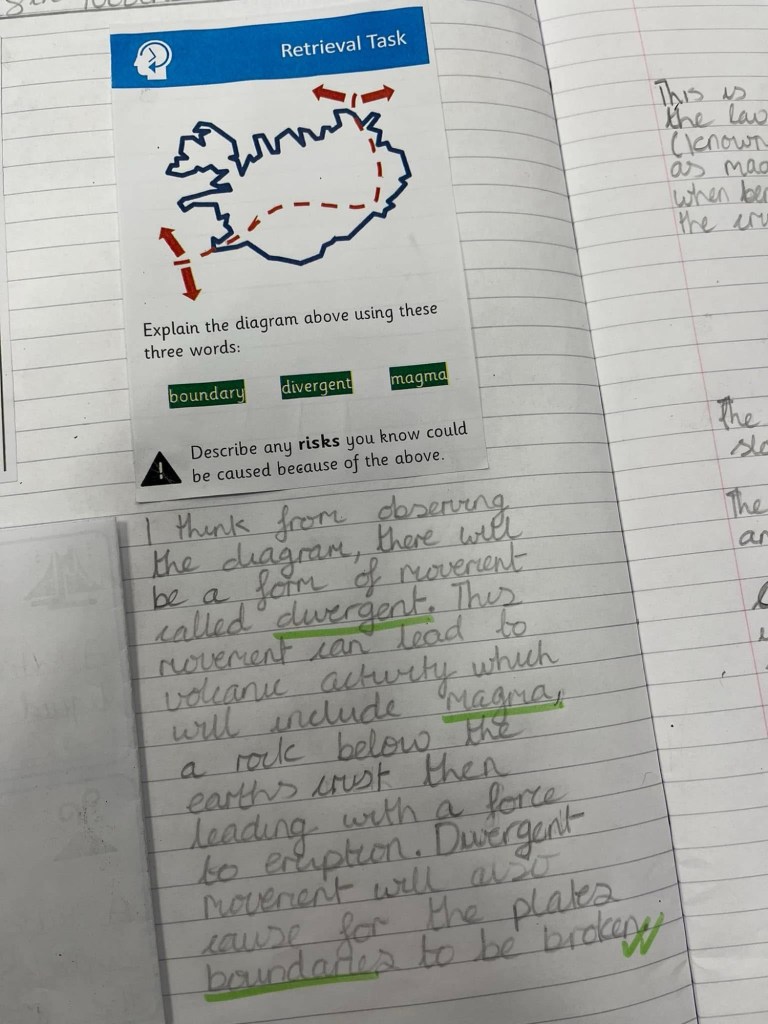

In geography, rather than asking “What type of plate boundary is found in Iceland?” aim for:

Tasks that encourage the children to link back to their learning visually. Instead of just recalling simple facts, this encourages a greater range of responses and allows children to write more or less depending on their level of understanding.

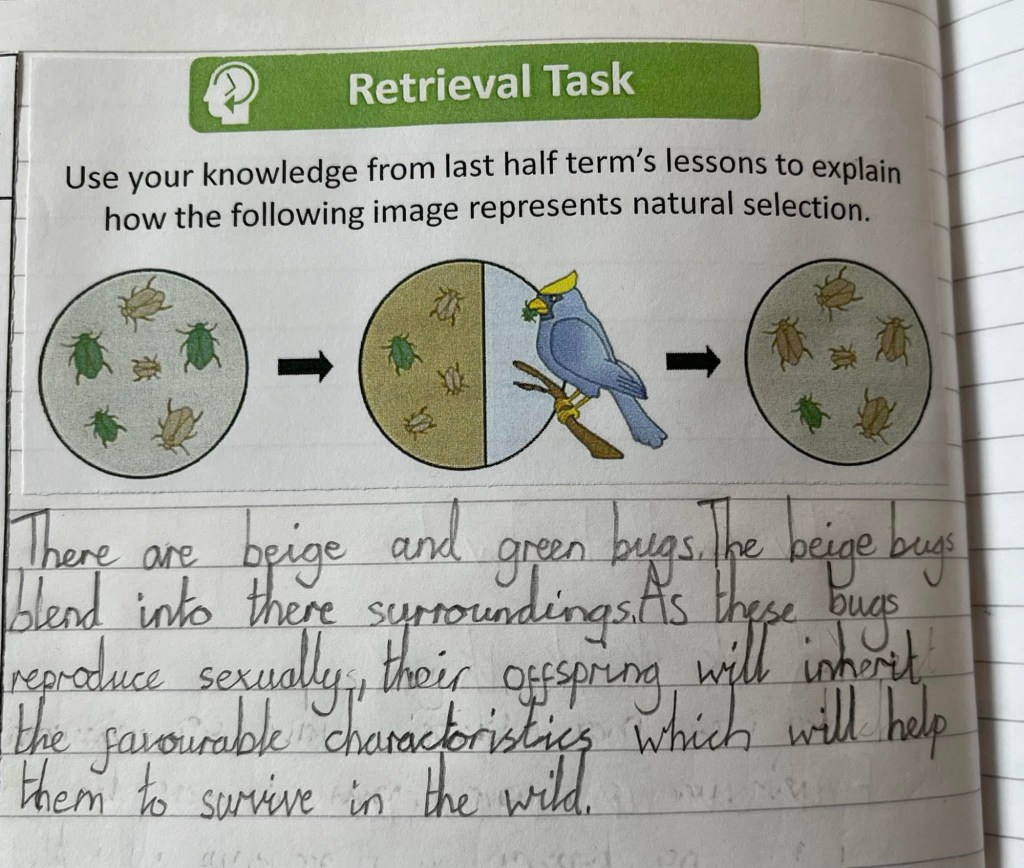

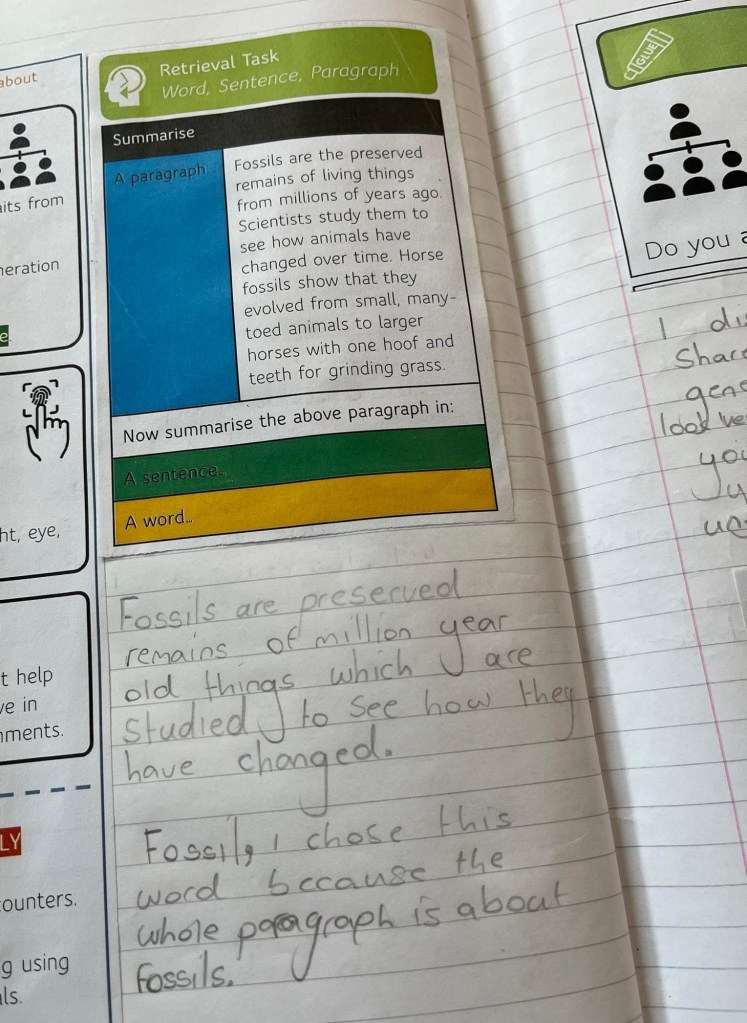

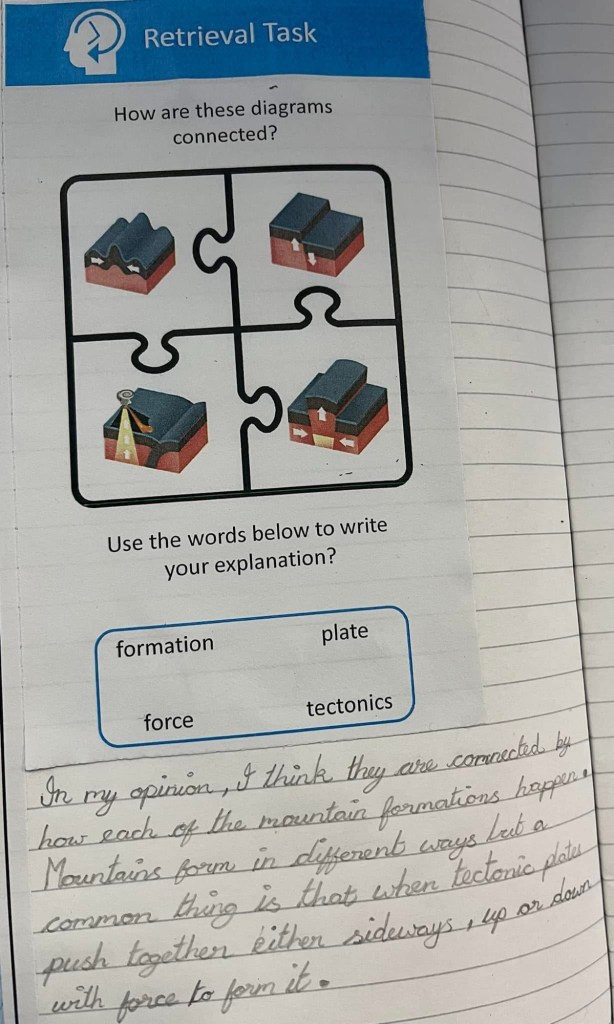

And in science, instead of “What is natural selection?” Aim to use tasks like this:

Which instead prompts children to apply their understanding to a new representation (an unfamiliar image sequence), requiring them to think, explain, and justify. Additionally, you can offer up vocabulary that could be used in the text.

By shifting retrieval tasks to focus on relationships between knowledge, we move from isolated recall to deeper disciplinary thinking.

Retrieval That Encourages Disciplinary Thinking

Different subjects require different types of retrieval. A historian retrieves knowledge differently from a scientist, and our retrieval tasks should reflect those differences.

In history, retrieval should involve sequencing, cause and consequence, and significance. Instead of “Who was Henry VIII’s second wife?”, ask:

“Why did Henry VIII’s marriages change England’s religion?”

In science, retrieval should involve conceptual understanding. Instead of “What are the three states of matter?”, ask:

“What would happen to a puddle of water on a hot day, and why?”

In maths, retrieval should encourage application and reasoning. Instead of “What is 7 x 8?”, ask:

“Tom says 7 x 8 is the same as 14 x 4. Is he correct? How do you know?”

When retrieval tasks mirror the way knowledge is used within a subject, we ensure children aren’t just memorising, they’re thinking like historians, scientists, and mathematicians.

The Issue with Mini Whiteboards in Retrieval Practice

Mini whiteboards are often used as a quick retrieval tool and this is a perfectly effective and reasonable strategy. However, there is research to suggest they may not be the most effective method for long-term retention. Whiteboards provide immediate feedback for teachers but lack individual accountability – once it’s wiped off (if it was written in the first place) there is no record of what was written, meaning children are not engaging in the full benefits of retrieval.

According to Agarwal and Bain’s research on retrieval practice (2020), writing answers down in books, rather than on whiteboards, strengthens memory because:

It creates a retrieval effort that lasts beyond the moment, children can refer back to their answers later.

It slows down thinking, allowing more cognitive engagement with the question.

It removes the ‘erasure effect’, where a child can quickly move on without reflecting on their response.

Even Rosenshine’s research into effective teaching principles highlights the importance of written rehearsal of knowledge, rather than just oral or quick-written responses. If retrieval is done solely on whiteboards, we risk prioritising performance over actual retention.

The Importance of Writing Retrieval in Books

Writing retrieval answers in books has been shown to improve retention more effectively than verbal responses or whiteboard work. Research by Karpicke & Blunt (2011) found that children who wrote their answers down remembered significantly more information than those who only read or spoke their responses.

This is because:

✅ Writing engages the generation effect, the idea that producing knowledge yourself enhances memory.

✅ Written answers force children to structure their thinking, making retrieval more effortful and, therefore, it can be more effective.

✅ They provide a permanent record, so children can revisit and build on previous retrieval work.

Kate Jones has frequently highlighted the need for retrieval tasks that have longevity, not just ‘show me and wipe away’ moments. By ensuring retrieval is recorded in books, we reinforce the learning process rather than just measuring short-term performance.

Retrieval as a Curriculum Design Tool

Perhaps the most overlooked aspect of retrieval is its role in shaping curriculum sequencing. If retrieval tasks consistently reveal gaps in understanding, it isn’t just an issue of memory, it’s a signal that something in the curriculum sequence may need adjusting.

When retrieval tasks show persistent misconceptions, it raises important curriculum questions:

Are key concepts being revisited often enough?

Are children being given enough opportunities to connect knowledge across subjects?

Are retrieval tasks too focused on fact recall rather than deeper application?

Retrieval should not just be a test of what children remember but a reflection on what has been effectively taught and understood.

Final Thoughts

Retrieval is a powerful tool, but only when used with intention. If we want retrieval to be effective, it must:

✅ Move beyond isolated fact recall and focus on connections.

✅ Reflect the way knowledge is used within different disciplines.

✅ Encourage metacognitive reflection.

✅ Be used as a tool for curriculum refinement, not just assessment.

✅ Be recorded in books rather than erased on whiteboards for greater retention.

Rosenshine and Kate Jones as well as many others have laid the groundwork for understanding retrieval as a powerful cognitive tool, but as teachers, it’s our role to ensure that retrieval tasks are meaningful, challenging, and embedded in ways that deepen children’s understanding.

Retrieval is something I love, not just as a practice, but as a mindset. It’s not about remembering more, but about thinking better. When done right, retrieval transforms learning from a process of recall into a process of reasoning, connection, and understanding.

Thanks for reading.

Karl (MRMICT)

Leave a comment