If you haven’t yet read the earlier instalments of this series, I encourage you to do so. Each one builds on the others, moving from curriculum to pedagogy, task design, and now to assessment. Links can be found below.

https://mrmict.com/2024/02/24/a-timeline-of-task-design-curriculum-is-crucial/

https://mrmict.com/2024/05/30/a-timeline-of-task-design-part-2-mastering-pedagogy/

https://mrmict.com/2024/08/01/a-timeline-of-task-design-part-3-tackling-the-task/

After a slight, hiatus, I have revisited my series of blog posts ‘The Timeline of Task Design.’ In an attempt to reorient ourselves allow me to explain the series so far. The first part of this series, I argued that curriculum is a kin to the “spine” of task design, the foundation on which everything else depends. In Part 2, I explored pedagogy—think of this as the movement that animates that spine. Part 3 focused on task design as the tangible bridge between the curriculum and classroom reality. Now, in this fourth and final instalment of this segment, we arrive at assessment.

If curriculum defines what children should know and pedagogy determines how it is taught, assessment allows us to evaluate its impact. I want to emphasise this, assessment allows us to evaluate the IMPACT of the curriculum. It is not to determine the success of a child. Yet assessment is not the end of the journey. Task design is cyclical, and assessment is the moment when we pause, reflect, and return to the beginning.

In reality my timeline above should have a very large arrow bringing us back to the beginning allow us to ask:

• Is the content correct?

• Is the instruction appropriate?

• Do the tasks reflect the curriculum’s intent?

To achieve this, assessment must do more than measure knowledge; it must deepen learning and offer insight into how effectively tasks and teaching have fulfilled the curriculum’s goals.

Assessment and the Clarity Model

Clarity in task design has been a something I have been considering for a while and I feel it needs to be included in this series. Inspired by Scott McCloud’s clarity diagram, ‘Clarity’ is what effective task design is. It is making clear the abstract concepts to be constructed by our young minds. Assessment is no exception. Effective assessment aligns with five critical “choices” in the clarity model:

1. Choice of Moment: Why are you assessing now? Does this moment feel natural within the learning sequence?

2. Choice of Frame: How are you assessing? Is the method aligned with the disciplinary focus of the unit?

3. Choice of Image: Are visual supports (e.g., models, diagrams) helping to reduce cognitive load and focus thinking?

4. Choice of Word: Are instructions precise and accessible? Does the assessment language match that of prior teaching?

5. Choice of Flow: Does the assessment fit seamlessly within the unit, building on prior tasks and leading naturally to the next phase of learning?

These choices ensure that assessment is not a bolt-on activity but an integral part of the learning process. Assessment shouldn’t bring up any unexpected surprises, this is why an effective retrieval and feedback strategy allows you to keep a running tab on what holes or misconceptions are developing.

Assessments

The Problem with Traditional Tools: Pre-Assessments and KWL Grids

In earlier parts of this series, I cautioned against tasks that feel purposeless or redundant, and this principle applies equally to assessment. Two of the most commonly used, yet least effective, tools are pre-assessments and KWL grids. I want to be clear this is not a judgement on anyone or school moreover a plea to move away from these practices.

I have been in the position, asking children to make a list of questions they want to have answered during the unit or the things they already know. There’s a falicy in this. Pre-assessments often feel like an attempt to “see what children know” before starting a unit. Yet they rarely provide meaningful insight.

1. Misleading Data: Children will more often than not naturally perform poorly on a pre-assessment for reasons unrelated to their understanding such as task unfamiliarity or retrieval failure.

2. Duplication of Effort: A well-sequenced curriculum already accounts for prior knowledge. Pre-assessments often confirm what we already know: that some children have gaps in understanding.

3. Lost Opportunity: Time spent on pre-assessments could be better spent building foundational knowledge through well-designed tasks.

KWL Grids

I feel it important to address these specifically. I still see people advocate them on Instagram and large sections of resources websites are dedicated to them. KWL (Know, Want to Know, Learned) grids promise to engage children in metacognition but often result in superficial or misguided outcomes.

1. Misconceptions in the ‘K’ Column: Children frequently list incorrect or vague ideas that require unpicking later.

2. Irrelevance in the ‘W’ Column: Questions like “Did Vikings have pets?” rarely align with the curriculum’s intent and whilst it might be nice to know for one or two children what purpose does it serve?

3. Surface-Level Responses in the ‘L’ Column: Children may write broad, unspecific statements that give little insight into their depth of understanding.

What Should We Do Instead?

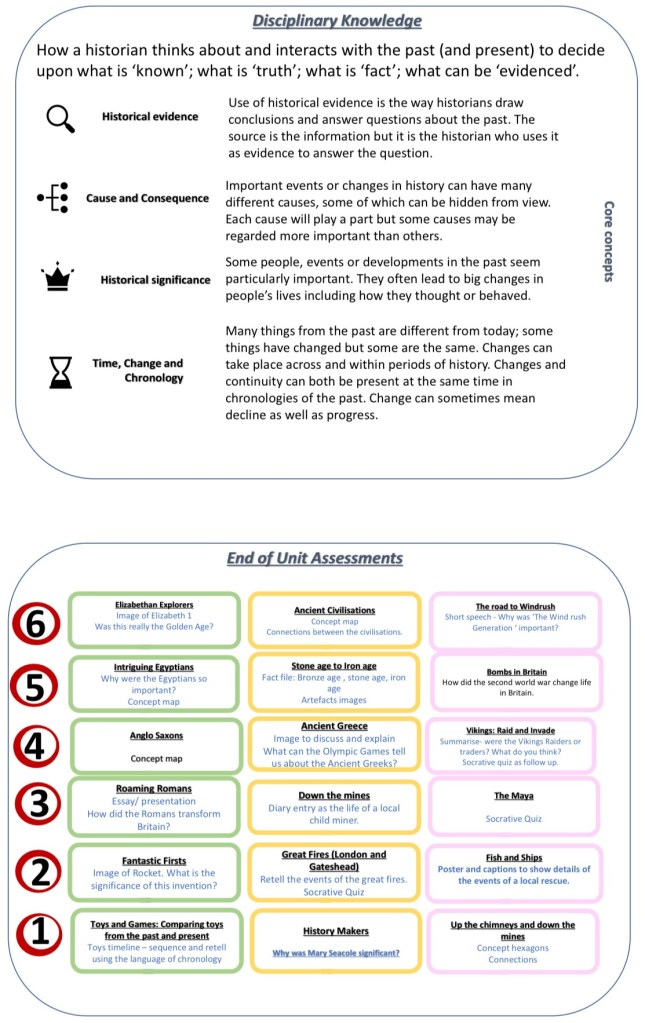

Effective assessment tasks should reflect the substantive and disciplinary knowledge central to the unit. In your curriculum, as shown in the attached images, each unit highlights key substantive knowledge (the “what”) and disciplinary knowledge (the “how”). This distinction is crucial when designing assessments.

Aligning Assessment with Disciplinary Focus

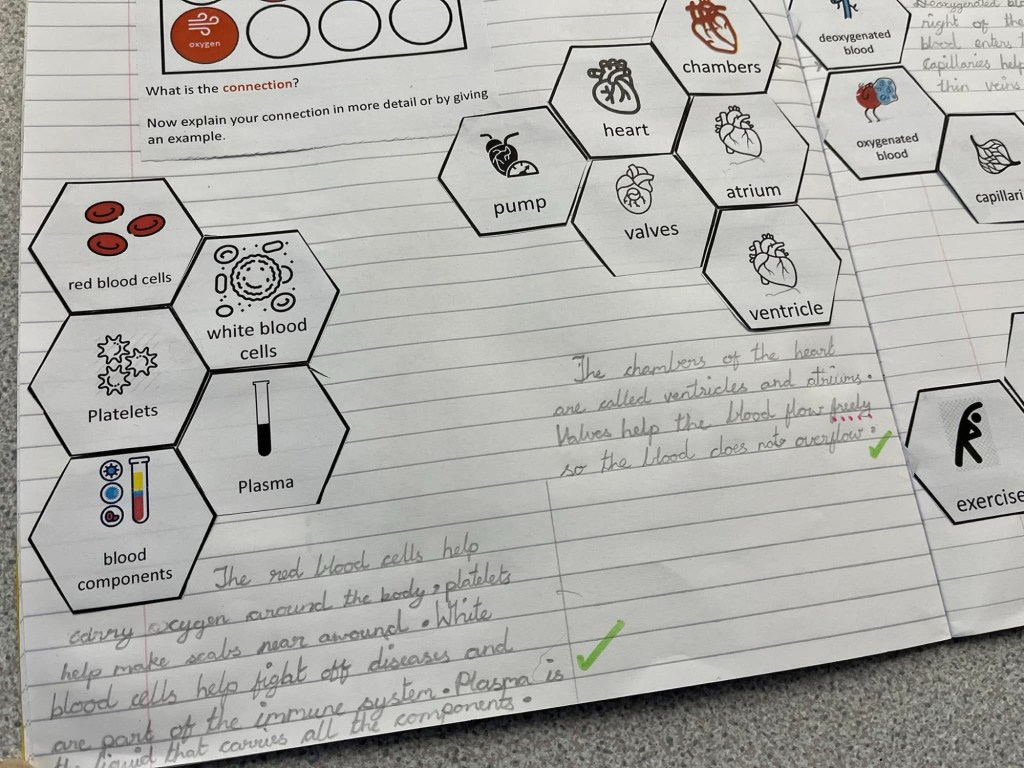

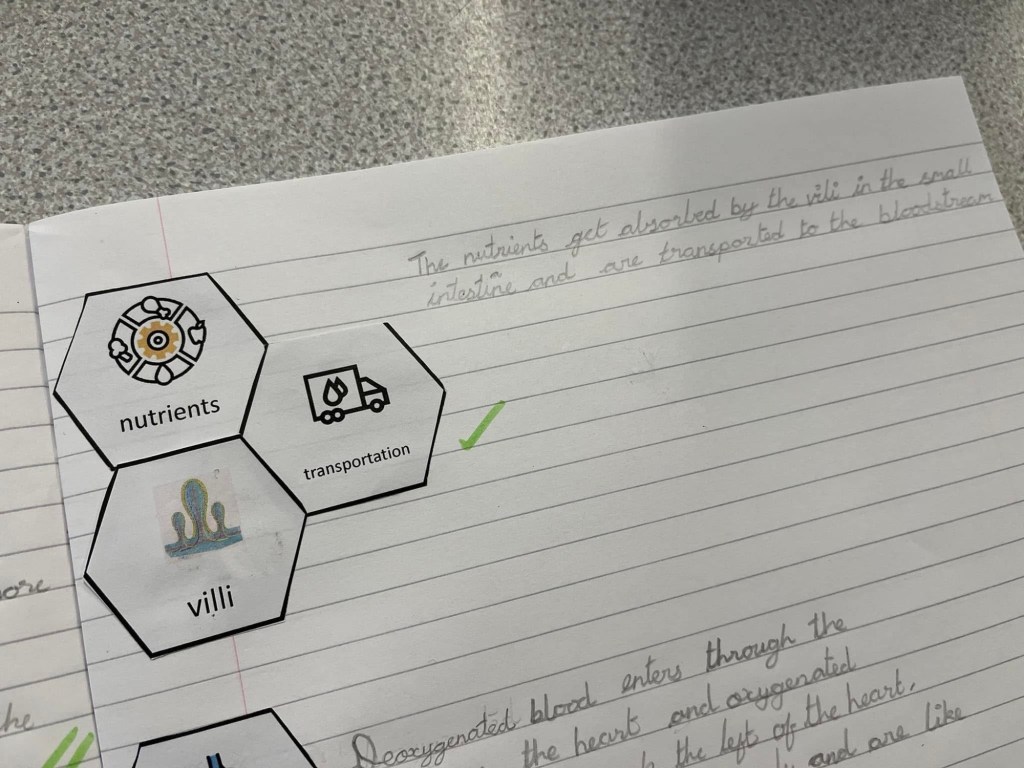

Some units, such as the circulatory system in science, have a heavy emphasis on substantive knowledge. For these, assessments like hexagon mapping can work well. Children might use hexagons to map concepts such as “oxygen,” “heart,” and “arteries,” creating a visual representation of how these elements connect.

The connections children make between these concepts offer insight into their disciplinary understanding—how well they grasp the system as a whole, not just its parts.

In history, disciplinary assessments might focus on cause and consequence or historical significance. For example, in a unit on Elizabethan exploration, children could use a timeline to evaluate how religious conflict and economic motivations shaped exploration.

Using Choice of Frame to Match the Discipline

Assessment methods should reflect the nature of the subject:

• In history, you could focus on tasks like concept maps or evaluative questions that encourage children to weigh evidence and construct arguments.

• In geography, use tasks like annotated maps or fieldwork analysis to highlight locational understanding.

• In science, emphasise processes like sequencing or modelling to demonstrate understanding of systems or cause and effect.

For example, your geography assessment outcomes show how tasks like creating ranking causes of deforestation align with the disciplinary focus of each unit. These tasks are not only assessments but also learning opportunities that deepen understanding.

Embedding Clarity in Task Design

Referencing the clarity model:

• Choice of Moment: Assessments should occur after children have had opportunities to practice and consolidate knowledge, not as an arbitrary starting point.

• Choice of Image: Use visual tools like diagrams or maps to scaffold thinking. For example, when assessing rivers and their uses, an annotated image can support children’s explanations, it should also be an image the children have encountered and not completely abstract from what they have experienced through the teaching. We make the mistake of giving a different visual or image to check if the children can transplant their understanding to this new image. This is not a fair test of understanding and leads to increased cognitive demand.

• Choice of Word: Ensure assessment language mirrors teaching. If children have been taught the term “plate tectonics,” avoid using “continental drift” unless both have been explicitly taught and linked.

The End of the Timeline, But Not the End of the Process

Assessment marks the “end” of the task design timeline, but it’s not a final destination. Task design is cyclical, and assessment should lead us back to the curriculum. This reflection is critical:

• Is the content correct? Are the substantive concepts accurate and well-chosen?

• Is the instruction appropriate? Did teaching methods align with the demands of the discipline?

• Do the tasks reflect the curriculum’s intent? Were they challenging, purposeful, and clear?

By asking these questions, we ensure that assessment doesn’t just measure learning—it improves it.

Final Thoughts

In this series, we’ve explored what I believe are the four key stages of task design: curriculum, pedagogy, tasks, and assessment. Together, they form a cycle of clarity and purpose.

Assessment, when designed thoughtfully, is not an add-on or an afterthought. It is the culmination of a sequence, a moment to reflect on what has been learned and how well our teaching has served the curriculum’s intent.

This is not the end of the timeline but rather a loop back to the beginning. Task design is a continuous process—one that evolves, improves, and refines itself with every cycle. It’s important to clarify, however, that ‘task design’ is not a verb. Recently, I’ve heard people ask, “Do you do task design in every lesson?” The answer is unequivocally yes—because task design encompasses everything we do. While it may have unintentionally become shorthand for thoughtful practice, it’s not just an action—it’s a framework for intentionality and purpose in teaching.

Join me for future discussions as we continue to explore what makes great teaching and learning.

Feel free to reach out on Twitter (X) @MRMICT or join our growing Facebook group to share your thoughts and ideas.

Leave a comment