Introduction

Before we start, if you haven’t already read the first two blogs in this series, I will include the link below for ease.

The purpose of this series is to illuminate the intricacies of task design, emphasising that effective task design involves more than meets the eye. In the first instalment, I reflected on the need for a high-quality, knowledge-led curriculum, underscoring the importance of being clear about what we want children to know and do. This forms the foundation of our curriculum. In the second, I focused on the significance of pedagogy, asserting that a high-quality curriculum is inextricable from an effective pedagogical strategy.

For the third and penultimate blog in the series, we will focus on the task itself. Task design, for me, is the meticulous process of crafting learning tasks that bridge the curriculum with real-world understanding in the classroom. This process goes beyond simply creating writing tasks or worksheets for labelling; it involves being mindful and purposeful in selecting activities that enable children to practice, attempt, or demonstrate their understanding effectively.

Understanding Task Design

When executed well, task design enhances the relationship between instruction, tasks, and assessment. While it can be part of lesson planning, task design encompasses all instructional tools, ensuring that tasks align with instruction rather than being hastily downloaded from a website and appended to the end of a lesson. Effective tasks should cater to the curriculum model and the diverse needs and perspectives of the children. This does not mean creating different tasks for different children but ensuring a range of variation and exposure within the lesson or sequence of lessons.

What Constitutes a Task?

Research helps us to consider what a task is. As presented by Doyle and Carter (1984), the curriculum appears in the classroom through tasks given by teachers—what I like to call the curriculum in real life. Tasks are essential for children to engage with and comprehend the subject matter within the curriculum. A task comprises several key components:

1. Product:

This is the output expected from children, such as filling in blanks on a worksheet, answering a set of test questions, or labelling work based on a particular objective or skill.

2. Operations:

These are the actions required to produce the product. Examples include copying words from a list, recalling information from previous lessons, applying rules (e.g., “Plural nouns use plural verbs”), or creating descriptive or creative text.

3. Resources:

These include the tools and aids children may use, such as referring to scaffolds in their book, consulting a word bank, engaging in peer discussions, or using equipment provided in class such as protractors.

4. Significance:

This refers to the importance of the task within the classroom. For instance, a daily grammar exercise might serve as a retrieval task, while a longer piece of writing may carry more weight and could act as an assessment.

The concept of “task” emphasises four critical aspects of classroom activities: the goal or end product, the conditions and resources available to accomplish the task, the cognitive operations involved in using these resources, and the significance of the work. These elements provide us with essential information about how to enable children to engage with the curriculum content. Consequently, tasks play a fundamental role in shaping children’s learning by communicating the curriculum’s expectations and requirements (Doyle, 1984).

This understanding clarifies what a task is and what is required to bring the curriculum to life. However, not all tasks are created equally. Recall tasks, such as cloze procedures or labelling, allow children to practice before moving beyond the guided practice stage. However, creating tasks that offer challenge is essential.

This blog by Elliot Morgan provides an insightful discussion on ‘challenge’ within tasks.

Morgan succinctly notes that challenge occurs “when prior knowledge meets an unfamiliar context.”

Crafting Thoughtful, Challenging, and Meaningful Tasks

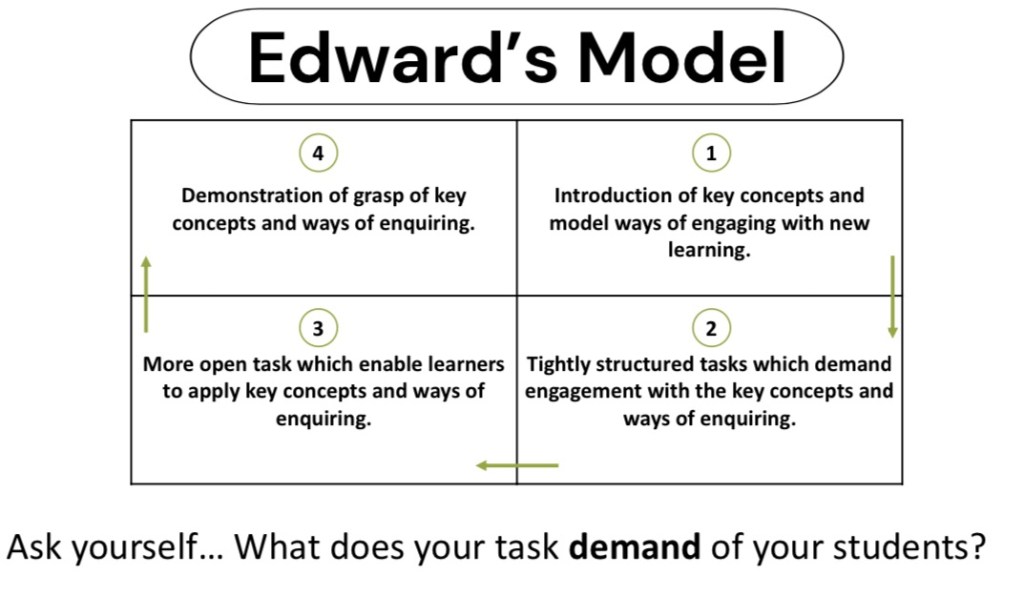

Edward’s Task Design Model provides a comprehensive framework for creating tasks that are thoughtful, challenging, and meaningful. This model emphasises the importance of intentionality in task creation, ensuring that every activity aligns with the curriculum, the discipline of each subject, and encourages deep thinking by the children, thereby ensuring engagement and learning.

Key Components of Edward’s Task Design Model

1. Introduction of Key Concepts and Model Engagement:

The foundation of Edward’s model starts with introducing key concepts and modelling ways of engaging with new learning. This stage involves careful consideration of pedagogical choices. Refer to part two of this blog series for an in-depth exploration:

It is essential to explain the essential ideas we aim to convey and demonstrate how to interact with them. For example, a lesson on earthquakes should explore plate tectonics, their movement, and its consequences. In my experience, using cards or rubber to model tectonic collisions and drift can aid in explaining these abstract concepts.

2. Open Tasks for Application:

Following the introduction, children are presented with more open tasks that enable them to apply key concepts and ways of enquiring. This exploration should involve pairs or trios, having had prior exposure to the concept or knowledge. These tasks encourage exploration and experimentation, allowing children to connect new knowledge with real-world situations and prior understanding. For instance, children might investigate a local ecosystem, recording their observations and comparing them to previously discussed concepts.

3. Tightly Structured Tasks for Deep Engagement:

The next phase involves tightly structured tasks that demand engagement with key concepts and ways of enquiring. These tasks are designed to challenge children to think critically and work systematically. An example could be a detailed study of the Ring of Fire and the connection between tectonic plate movement and the prevalence of earthquakes in this region.

4. Demonstration of Grasp of Key Concepts:

Finally, children demonstrate their grasp of the key concepts and ways of enquiring. This stage is crucial for assessing their understanding and ability to apply what they have learned. For example, providing pictures of the Ring of Fire and Iceland, or a series of hexagons with connected concepts, allows children to showcase their analysis of tectonic plate movements and their consequences, including detailed explanations of various interactions.

By understanding and thoughtfully designing tasks, teachers can ensure that children are not only completing activities but are also engaging meaningfully with the curriculum, thus enhancing their overall learning experience. A simple question to ask yourself is, “What does your task demand of your children?”

Key Considerations in Task Design

In planning a lesson, consider the following questions:

– Oral Rehearsal: What will the children orally rehearse? Are the partners correct, or should there be trios for partner talk?

An effective task that helped children internalise the process of blood distributing oxygen and nutrients throughout the body was demonstrated here:

– Word Breakdown: Do you carefully break down words through morphology or etymology?

Always ensure that children actively interact with key vocabulary, breaking these down into relatable chunks. In a recent history lesson we explored the meaning and origin of the word ‘dooms’

– Whiteboard Usage: Are the whiteboards blank, and why? Is there a need to provide a thinking model?

Research suggests that blank whiteboards can create anxiety and restrict learning. Providing graphic organisers or thinking models allows children to think within their external memory field, again engaging actively with the knowledge.

– Model Texts: If there is going to be writing, do children need access to a model text, particularly disciplinary texts?

Hearing Mary Myatt speak about the importance of using ‘beautiful texts’ inspired me to include high-quality, disciplinary texts wherever possible. The thread below illuminates this further:

These rhetorical questions illustrate the depth of thought required in task design. Many educators may address these aspects intrinsically, yet it is crucial to consciously reflect on these elements to ensure effective learning experiences.

The Purpose of Task Design

The reason I established the group and networks is to foster the creation of better tasks and learning opportunities. There is a clear appetite for thoughtful task design among educators. My goal is to encourage teachers to think critically before adopting a seemingly attractive task from a large website. Some tasks may not always fit perfectly or align with the relationship between disciplinary and substantive knowledge, but this challenge is part of the fun and creativity in teaching.

Task Design and Instruction

Writing tasks, for instance, have evolved as we have become more fluent in our task design. While Rosenshine’s principles focus on effective instruction, task design encompasses the stages before, during, and after instruction. This comprehensive approach ensures that tasks are not only engaging but also meaningful and aligned with instructional goals.

Conclusion

In summary, effective task design is about more than just filling lesson time with activities. It requires a deep understanding of the curriculum, thoughtful planning, and a keen awareness of children’s needs. By integrating these elements, we can create tasks that not only support learning but also inspire and challenge our children.

Join our growing Facebook group to contribute to the ongoing discussion on task design.

Feel free to get in touch to offer feedback, constructive criticism, or ask any questions on Twitter (X) @MRMICT.

Leave a comment